基于干细胞的前交叉韧带损伤修复疗法

前交叉韧带(ACL)损伤的发生率逐渐增加,在美国,估计每年进行20万台ACL重建手术[1]。在过去有报告显示,ACL缝合修复的疗效不佳,这表明ACL的修复愈合潜能较差[2-7]。因此,ACL损伤进行ACL重建手术作为替代治疗方法。如今,随着解剖隧道建立、移植物选择、移植物固定时最佳初始张力等手术技术的改进[8,9],ACL重建手术被认为是治疗的金标准,成功率高达80% [10-14]。然而,根据一项荟萃分析结果,只有40%的患者可以实现完全康复,与手术技术无关[15]。另一项多中心队列研究显示,足球运动员在ACL重建术后需要平均7个月左右的时间(范围5-24个月)才能够恢复比赛[16]。此外,通过显微镜观察自体髌腱移植的ACL重建术,自体髌腱移植物与自体ACL的纤维不同,即使术后1年其结构仍未完全成熟[17]。一些研究报道了与ACL重建相关的一些问题,如本体感觉差,术后肌无力、获取供体的并发症、无法恢复正常运动,以及潜在的早期骨关节炎进展[18-21]。考虑到这些与ACL重建有关的局限性,需要有新的治疗方法。

在几个可能的方案中,生物操纵可能是一个可行的选项,这包括生长因子、富血小板血浆(PRP)、干细胞和生物支架的应用。已有研究结合这些方式,加速ACL的修复和再生。具体来说,基于干细胞组织再生的潜能,干细胞疗法已经得到了高度关注。干细胞有多种类型,如胚胎干细胞、诱导多能干细胞和间充质干细胞(mesenchymal stem cell ,MSC)。在这些干细胞中,MSCs的研究最为广泛,因为其分离相对容易、安全,同时其多能性和增殖能力强[22-24]。因此,这篇综述文章的目的是概述目前基于干细胞的前交叉韧带修复疗法的理念。

前交叉韧带的愈合能力

撕裂前交叉韧带的缝合修复首次报道于1895年。随后又进行了多项研究。这些报道表明,初次ACL缝合修复后只有三分之一的患者有良好的疗效[3-5]。此外,长期随访研究表明,失败率高达90% [6,7]。因此在过去40年中,基本上被前交叉韧带重建术所取代。相反,最近的一项研究报道显示,在最初5年内有良好疗效的患者在术后30年仍保持良好的效果[25]。这表明通过优化愈合环境来提高ACL的修复具有潜力。

为了优化修复潜能,可能需要考虑内在因素和环境因素[26]。就内在因素而言,一般认为ACL的原位可修复能力差。过去的一些研究表明,与其他韧带和肌腱相比,ACL修复过程中生长因子、细胞数量和分子表达都有所下降[27-33]。然而,对人类ACL的体外愈合研究表明,保留滑膜的损伤ACL具有与半腱肌腱相当的愈合能力[34]。此外,在ACL残端内,包括滑膜细胞在内的一些细胞对受伤的软组织具有修复潜能,但在另外一项体外研究中,股骨和胫骨残端之间没有组织桥接[28]。这些结果表明,人类ACL具有一定的内在愈合能力,滑膜可能在启动ACL修复中发挥着重要作用。因此,ACL修复的不良临床疗效不仅归因于韧带本身的愈合潜能差,同时还归因于其他环境因素,包括机械环境、炎症状况、血液供应、营养输送和生长因子的供应[28,35-39]。

基于细胞的前交叉韧带修复疗法

为了提高前交叉韧带的修复能力,通过体外和动物实验研究了基于细胞的前交叉韧带修复[40-42]。间充质干细胞是广泛分布于多种组织中的成体干细胞,具有多向分化潜能和自我更新能力。间充质干细胞可以分化为软骨细胞、脂肪细胞或成骨细胞等中胚层相关细胞的前体细胞。在体内,已证实间充质干细胞通常定位于血管周围区域[40]。目前公认的是间充质干细胞也存在于前交叉韧带中[43,44]。

体外研究

过去使用ACL来源的成纤维细胞的组织工程方法已被报道,并且具有一定前景[29,32,45]。但是,这种成纤维细胞在体外生长速度缓慢,可能会限制其在实际中的应用[22,46]。尤其是在体外比较关节内和关节外韧带来源的细胞[29,31],ACL来源的细胞比内侧副韧带来源的细胞细胞分裂率和迁移率更低。近年来的研究表明,骨髓间充质干细胞(Bone mesenchymal stem cells,BMSCs)的增殖能力明显高于ACL来源的成纤维细胞[22,47]。事实上,BMSCs已经能够在生长因子的作用下进行韧带定向分化[23,48-53]。

脂肪来源的干细胞(Adipose-derived stem cells,ASCs)也被作为ACL修复的另外一种MSCs选择。体外研究中,猪的ASCs能刺激ACL纤维母细胞增殖和胶原前体的生成[54],而人的ASCs结合生长因子不能激活其向韧带分化的潜能[55]。

就源自滑膜的间充质干细胞(Mesenchymal stem cells derived from synovium,SMSCs)而言,除了一例ACL重建的报道外,还没有关于其在ACL修复领域的报道[56]。然而,SMSCs的增殖和分化潜能比其他组织来源的MSCs高,这一点已得到证实[57-60],因此,SMSCs可作为ACL修复的替代方案。

利用来源于ACL的干细胞进行ACL修复的体外研究报道较少。只有两项研究报道 [43-44],在适当的培养条件下,ACL来源的干细胞和人类BMSCs相似,这表明这些ACL来源的细胞可能作为ACL修复的替代来源。

动物实验

关节内注射间充质干细胞

Morito等人[61]评价了兔关节腔内注射滑液来源的MSCs后MSCs的定位。他们发现,MSCs在ACL损伤后进入滑液,与正常的ACL相比,在损伤的ACL中发现更多的MSCs。他们的研究结果表明,MSCs通常不存在于完整的ACL中,而是存在于损伤的ACL中。在先前的其他动物研究中,MSCs关节内注射作为一种生物治疗方法应用于动物ACL部分损伤的治疗中[26,62]。Kanaya等人[26]发现,部分撕裂的ACL缝隙被修复组织所覆盖,注射后4周即可检测到BMSCs,而未注射BMSCs的断裂区域随着时间的增加而回缩,缝隙仍然存在。在他们的报告中,在术后4周时注入BMSCs后的股骨-胫骨复合体的极限失败载荷明显高于未注射BMSCs组。Oe等人[62]还发现,在横断ACL内侧半后,将新鲜的BMSCs注入膝关节,注入后4周期组织学和生物力学测试结果与正常ACL几乎相同。在这两项研究中,BMSCs在注射4周后仍保留在修复的ACL中[26,62]。目前还不清楚注射后的BMSCs是否通过基质合成直接参与修复组织,还是通过调节修复环境来发挥滋养作用。但是,BMSCs的关节内注射可能会加速部分撕裂ACL的愈合,因此这种使用BMSCs的治疗方法可能是促进ACL尤其是部分撕裂的患者ACL修复的一种选项。

载有MSCs的支架

多项报道证实了载有BMSCs的支架可以促进断裂的ACL再生[51,63-65]。大多数研究表明,BMSCs和支架对ACL的修复具有积极作用。与ACL成纤维细胞相比,BMSCs及其支架在细胞增殖、GAG分泌、韧带相关细胞外基质(Extracellular matrix,ECM)基因和蛋白质表达以及体内生存能力等方面均具有明显优势[63]。组织学观察也表明,MSCs分布在整个再生的韧带上,并表现出成纤维细胞的形态,更进一步,参与了腱骨止点直接的重建[50]。在过去的另一项研究中,将BMSCs种植在I型胶原支架上治疗ACL损伤可以促进韧带的再生,而单纯缝合组和不载细胞的I型胶原支架组却没有观察到韧带再生[64]。然而,Proffen等人的研究却显示,[65]加入了ASCs和ECM的支架,在ACL愈合的生物力学或组织学特性方面并没有得到明显改善。

结合间充质干细胞的ACL重建

关于使用MSCs促进ACL重建,已经有了一些研究[56,66-70]。在兔模型中,使用BMSCs在半腱肌腱移植物表面改性进行ACL重建可以促进ACL正常软骨止点的形成,而并非胶原纤维和瘢痕组织[66]。BMSC增强的ACL重建也显示出明显优于单纯ACL重建的生物力学特性。然而,Ju等人[56]将SMSCs植入到腱骨界面,结果显示SMSCs可以促进胶原蛋白的产生,从而使腱-骨界面形成牢固的连接,而不是形成纤维软骨。在他们的研究中,细胞的作用不是纤维蛋白封闭剂,而是骨胶原凝胶,这是没有形成纤维软骨的原因之一,与使用BMSCs的结果不同。由于结果不一致,因此需要额外的研究,最好是大动物模型,研究MSCs是否可以促进ACL移植物的骨整合。

在同种异体移植物ACL重建中,有一项研究评估了细胞和基因治疗技术的疗效[71]。 组织学观察表明,植入BMSCs或PDGF-B转染的MSCs可以促进ACL内的细胞浸润,增强创面的胶原沉积。类似地,Nakamura等人[72]报道,在大鼠模型中直接进行体内PDGF-B基因转染后,髌韧带创面的血管化增加和胶原蛋白沉积增强。因此,基因转染技术结合MSCs移植,可以进一步有效地优化ACL的修复和移植物重塑。这种联合疗法的临床应用还需要进一步的研究来积累证据。

临床应用

同样地,在体外和体内的动物研究中,关于MSCs细胞疗法在ACL修复中的临床应用也没有足够的报道。迄今为止,以细胞为基础的治疗方法仅限于经皮关节内注射自体BMCs,或通过股骨髁的微骨折输送BMCs。Centeno等人[73]报告了一个小的病例系列,对ACL部分撕裂或完全断裂回缩小于1cm的患者进行关节内注射自体BMCs。基于良好的磁共振成像(MRI)和临床结果,他们认为这种治疗方法是可行的。然而,其缺乏前向松弛等客观依据支持。此外,也有关于应用微骨折BMCs技术进行前交叉韧带愈合效果的研究。Steadman等人[74]首次报道了在骨骼未发育成熟的运动员中修复近端完全撕裂的ACL,平均随访69个月,微骨折会导致血凝块形成和其后包含BMSCs的血肿形成。术后临床评分和活动水平与ACL损伤前相当。仪器评估前向松弛得到了充分的改善(术前5mm到术后2mm),13例患者中有23%再次受伤并进行了ACL重建手术。最近,同一研究小组结果显示,活跃的中年患者在进行相同的手术后,平均随访7.6年[75], 与他们之前的报告结果类似,临床效果良好,48例患者中只有8.9%的患者需要进行再次的ACL重建。这些研究表明,通过选择合适的患者,微骨折的愈合反应可以恢复膝关节的稳定性和关节功能。Gobbi等人[76]报告,缝合近端部分撕裂的ACL并进行了微骨折后,韧带断端的间距缩小,连续性恢复,招募从骨髓穿刺中获得的BMSCs以促进愈合。BMSCs和注射的PRP可能作为前体细胞和生长因子的来源。此外,Gobbi等人[77]评估了ACL近端部分撕裂缝合修复后的效果,BMSCs和注射富血小板血浆可作为前体细胞和生长因子的来源。结合微骨折和在修复部位注射PRP后,根据中期随访结果,50名运动员中有78%可以恢复正常的体育活动,前向松弛度的侧-侧差异明显减少(术前4.1mm,术后1.4mm),临床评分良好,但有4名患者经历了再次撕裂,1名患者有残余的松弛,导致5年随访时的存留率为90%。尽管有良好的临床效果,但他们强调,并非所有的ACL病变都可以用这种技术治疗,患者的选择是至关重要的,应遵循严格的纳入标准。最后,他们得出结论,在经过严格选择的急性前交叉韧带部分撕裂病变的患者中,使用这种一期ACL修复的手术技术可以得到良好的临床效果[77]。

所有这些研究都只是个案,但MSCs确实具有可以促进ACL损伤修复的潜力。扩大这些方法的适用范围需要进一步的研究和更多的证据。

其它ACL生物学修复治疗

与基于MSCs的方法一样,包括转化生长因子β1 (Transforming growth factor beta1 ,TGF-β1)、成纤维细胞生长因子-2 (Fibroblast growth factor-2,FGF-2)、生长因子和碱性成纤维细胞生长因子(bFGF)在内的几种生长因子可能通过调控细胞活性,如MSCs在修复过程中增殖和分化为韧带祖细胞,潜在地改善ACL的修复愈合[78-82]。此外,已知PRP含有这些生长因子,并研究了PRP对ACL愈合的影响。虽然没有明确的PRP对ACL愈合具有积极作用的报道[83,84],但一项人体临床研究[85]表明PRP可促进急性部分撕裂ACL的修复。这项临床研究显示所有患者MRI上ACL残端完整,经KT-1000评估前向松弛正常。近年来,生物支架结合PRP被用于ACL的修复。体内动物实验表明,单纯胶原支架对ACL的修复无明显作用[86],但胶原支架与自体血小板复合使用对ACL的修复具有明显的改善作用[87]。在一项临床研究中,Murray等人[88]报道了使用以ECM为基础的胶原支架与自体全血增强ACL修复的效果。他们通过MRI证实了修复后ACL的连续性,术后3个月,ACL修复后与自体腘绳肌腱ACL重建术后的临床结果相当。他们还发现,ACL修复组术后3个月的腘绳肌力量明显优于ACL重建组。这项研究仅纳入受伤后不到1个月的新鲜ACL撕裂,在术前MRI上至少有50%的韧带连在胫骨上。因此,如果仔细筛选病例,这种生物支架技术可以用于一些ACL损伤的修复,需要更详细的对照研究来验证这种治疗方法的可行性。

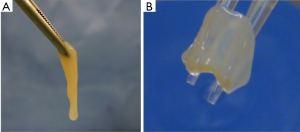

一般来说,支架在受保护的三维环境[89]下为受损部位提供机械稳定性,同时允许细胞黏附与增殖。然而,仍然有一些担忧支架中含有的动物或化学高分子材料,这些材料可能会影响支架长期的耐久性和安全性[90-93]。因此,无支架组织工程的概念得到了关注。最近的研究证明了由滑膜间充质干细胞衍生的无支架组织工程构建物(TEC)在软骨和半月板修复中的可行性(图1)[94-98]。TEC含有高密度的未分化的间充质干细胞,其三维基质是由间充质干细胞自身合成的,在猪软骨缺损模型中,6个月后可促进软骨修复,具有一定的机械性能[99,100]。Deie等人[34]认为,滑膜在提高韧带愈合能力方面起到重要作用。在这方面,用来自滑膜的TEC来促进韧带愈合是比较合理的。当然,包括TEC在内的生物学方法在促进ACL修复和移植物重塑方面的临床应用还需要进一步的研究。

结论

前交叉韧带重建被认为是前交叉韧带损伤治疗的金标准。但在临床上,有限的患者需要几个月的时间才能完全恢复运动。此外,在显微镜下,ACL重建的自体移植物在术后1年内仍未成熟,与正常ACL纤维明显不同。因此,随着组织工程技术的发展,使用间充质干细胞的新生物技术被应用于ACL的修复。历史上,由于环境因素、周围组织和血供不足以及ACL愈合能力差等原因,ACL缝合修复在临床上并不成功。最近的实验和临床研究表明,无论是否使用支架、PRP或其他生物制剂,BMSCs治疗急性和部分撕裂ACL都具有很好的疗效。这些使用MSCs的细胞疗法可能是改善ACL愈合的一个潜在有用工具。然而,患者的选择是必须的,严格的纳入标准也是非常重要的。并非所有ACL撕裂的患者都可以用这些细胞疗法治疗。要使用MSCs修复前交叉韧带的完全撕裂,未来还需要进一步的研究和更多的证据。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aoj.2017.11.03). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), Vanderbilt University, United States. Prognosis and predictors of ACL reconstruction—a multicenter cohort study. Available online: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00463099

- Robson AW. VI. Ruptured crucial ligaments and their repair by operation. Ann Surg 1903;37:716-8. [PubMed]

- Wittek A. Über Verletzungen der Kreuzbänder des Kniegelenkes. Dtsch Z Chir 1927;200:491-515. [Crossref]

- Wittek A. Replacement of the cruciate ligament with patellar tendon. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1935;65:103-4.

- Eppley BL, Woodell JE, Higgins J. Platelet quantification and growth factor analysis from platelet-rich plasma: implications for wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;114:1502-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feagin JA Jr, Curl WW. Isolated tear of the anterior cruciate ligament: 5-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 1976;4:95-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cabaud HE, Rodkey WG, Feagin JA. Experimental studies of acute anterior cruciate ligament injury and repair. Am J Sports Med 1979;7:18-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shino K, Mae T, Tachibana Y. Anatomic ACL reconstruction: rectangular tunnel/bone-patellar tendon-bone or triple-bundle/semitendinosus tendon grafting. J Orthop Sci 2015;20:457-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu FH, van Eck CF, Tashman S, et al. Anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a changing paradigm. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:640-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shelbourne KD, Klootwyk TE, Wilckens JH, et al. Ligament stability two to six years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous patellar tendon graft and participation in accelerated rehabilitation program. Am J Sports Med 1995;23:575-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gobbi A, Francisco R. Factors affecting return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon and hamstring graft: a prospective clinical investigation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006;14:1021-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hospodar SJ, Miller MD. Controversies in ACL reconstruction: bonepatellar tendon-bone anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction remains the gold standard. Sports Med Arthrosc 2009;17:242-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spindler KP, Parker RD, Andrish JTMOON Group, et al. Prognosis and predictors of ACL reconstructions using the MOON cohort: a model for comparative effectiveness studies. J Orthop Res 2013;31:2-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gobbi A, Mahajan V, Karnatzikos G, et al. Single-versus double-bundle ACL reconstruction: is there any difference in stability and function at 3-year follow-up? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:824-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Biau DJ, Tournoux C, Katsahian S, et al. ACL reconstruction: a meta-analysis of functional scores. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;180-7. [PubMed]

- Brophy RH, Schmitz L, Wright RW, et al. Return to play and ACL injury risk after ACL reconstruction in soccer athletes from the Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) group. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:2517-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abe S, Kurosaka M, Iguchi T, et al. Light and electron microscopic study of remodeling and maturation process in autogenous graft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 1993;9:394-405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gobbi A, Domzalski M, Pascual J, et al. Hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: is it necessary to sacrifice the gracilis? Arthroscopy 2005;21:275-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pitman MI, Nainzadeh N, Menche D, et al. The intraoperative evaluation of the neurosensory function of the anterior cruciate ligament in humans using somatosensory evoked potentials. Arthroscopy 1992;8:442-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Porat A, Roos EM, Roos H. High prevalence of osteoarthritis 14 years after an anterior cruciate ligament tear in male soccer players: a study. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:269-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, et al. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:1756-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van Eijk F, Saris DB, Riesle J, et al. Tissue engineering of ligaments: A comparison of bone marrow stromal cells, anterior cruciate ligament, and skin fibroblast as cell source. Tissue Eng 2004;10:893-903. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen J, Altman GH, Karageorgiou V, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cell and ligament fibroblast responses on RGD-modified silk fibers. J Biomed Mater Res A 2003;67:559-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Centeno CJ, Schultz JR, Cheever M, et al. Safety and complications reporting update on the re-implantation of culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells using autologous platelet lysate technique. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2011;6:368-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor DC, Posner M, Curl WW, et al. Isolated tears of the anterior cruciate ligament: over 30-year follow-up of patients treated with arthrotomy and primary repair. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:65-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kanaya A, Deie M, Adachi N, et al. Intraarticular injection of mesenchymal stromal cells in partially torn anterior cruciate ligaments in a rat model. Arthroscopy 2007;23:610-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spindler KP, Clark SW, Nanney LB, et al. Expression of collagen and matrix metalloproteinases in ruptured human anterior cruciate ligament: an in situ hybridization study. J Orthop Res 1996;14:857-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray MM, Martin SD, Martin TL, et al. Histological changes in the human anterior cruciate ligament after rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000;82-A:1387-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagineni CN, Amiel D, Green MH, et al. Characterization of the intrinsic properties of the anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligament cells: an in vitro cell culture study. J Orthop Res 1992;10:465-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi K, Healey RM, Sah RL, et al. Novel method for the quantitative assessment of cell migration: a study on the motility of rabbit anterior cruciate (ACL) and medial collateral ligament (MCL) cells. Tissue Eng 2000;6:29-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amiel D, Nagineni CN, Choi SH, et al. Intrinsic properties of ACL and MCL cells and their responses to growth factors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1995;27:844-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper JA, Bailey LO, Carter JN, et al. Evaluation of the anterior cruciate ligament, medial collaterial ligament, Achilles tendon and patellar tendon as cell sources for tissue-engineered ligament. Biomaterials 2006;27:2747-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Geiger MH, Green MH, Monosov A, et al. An in vitro assay of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and medial collateral ligament (MCL) cell migration. Connect Tissue Res 1994;30:215-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deie M, Ochi M, Ikuta Y. High intrinsic healing potential of human anterior cruciate ligament. Acta Orthop Scand 1995;66:28-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frank C, Schachar N, Dittrich D. Natural history of healing in the repaired medial collateral ligament. J Orthop Res 1983;1:179-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frank C, Amiel D, Woo SL, et al. Normal ligament properties and ligament healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1985;15-25. [PubMed]

- Bray RC, Leonard CA, Salo PT. Vascular physiology and long-term healing of partial ligament tears. J Orthop Res 2002;20:984-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pujol N, Colombet P, Cucurulo TFrench Arthroscopy Society (SFA), et al. Natural history of partial anterior cruciate ligament tears: a systematic literature review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2012;98:S160-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray MM, Fleming BC. Biology of anterior cruciate ligament injury and repair: Kappa Delta Ann Doner Vaughn Award paper 2013. J Orthop Res 2013;31:1501-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caplan AI. All MSCs are pericytes? Cell Stem Cell 2008;3:229-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res 1991;9:641-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells: the past, the present, the future. Cartilage 2010;1:6-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steinert AF, Kunz M, Prager P, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell characteristics of human anterior cruciate ligament outgrowth cells. Tissue Eng Part A 2011;17:1375-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng MT, Yang HW, Chen TH, et al. Isolation and characterization of multipotent stem cells from human cruciate ligaments. Cell Prolif 2009;42:448-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tischer T, Vogt S, Aryee S, et al. Tissue engineering of the anterior cruciate ligament: a new method using acellularized tendon allografts and autologous fibroblasts. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2007;127:735-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scherping SC Jr, Schmidt CC, Georgescu HI, et al. Effect of growth factors on the proliferation of ligament fibroblasts from skeletally mature rabbits. Connect Tissue Res 1997;36:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ge Z, Goh JC, Lee EH. The effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and fascia wrap application to anterior cruciate ligament tissue engineering. Cell Transplant 2005;14:763-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cristino S, Grassi F, Toneguzzi S, et al. Analysis of mesenchymal stem cells grown on a three-dimensional HYAFF 11-based prototype ligament scaffold. J Biomed Mater Res A 2005;73:275-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heckmann L, Schlenker HJ, Fiedler J, et al. Human mesenchymal progenitor cell responses to a novel textured poly(L-lactide) scaffold for ligament tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2007;81:82-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fan H, Liu H, Wong EJ, et al. In vivo study of anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using mesenchymal stem cells and silk scaffold. Biomaterials 2008;29:3324-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li H, Chen C, Ge Y, et al. Spray-painted human fibronectin coating as an effective strategy to enhance graft ligamentization of a polyethylene terephthalate artificial ligament. Biotechnol Lett 2014;36:1079-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Canseco JA, Kojima K, Penvose AR, et al. Effect on ligament marker expression by direct-contact co-culture of mesenchymal stem cells and anterior cruciate ligament cells. Tissue Eng Part A 2012;18:2549-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haddad-Weber M, Prager P, Kunz M, et al. BMP12 and BMP13 gene transfer induce ligamentogenic differentiation in mesenchymal progenitor and anterior cruciate ligament cells. Cytotherapy 2010;12:505-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Proffen BL, Haslauer CM, Harris CE, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells from the retropatellar fat pad and peripheral blood stimulate ACL fibroblast migration, proliferation, and collagen gene expression. Connect Tissue Res 2013;54:14-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eagan MJ, Zuk PA, Zhao KW, et al. The suitability of human adipose-derived stem cells for the engineering of ligament tissue. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2012;6:702-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ju YJ, Muneta T, Yoshimura H, et al. Synovial mesenchymal stem cells accelerate early remodeling of tendon-bone healing. Cell Tissue Res 2008;332:469-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi Y, Sekiya I, Yagishita K, et al. Comparison of human stem cells derived from various mesenchymal tissues: superiority of synovium as a cell source. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2521-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shirasawa S, Sekiya I, Sakaguchi Y, et al. In vitro chondrogenesis of human synovium-derived mesenchymal stem cells: optimal condition and comparison with bone marrow-derived cells. J Cell Biochem 2006;97:84-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mochizuki T, Muneta T, Sakaguchi Y, et al. Higher chondrogenic potential of fibrous synovium-and adipose synovium-derived cells compared with subcutaneous fat-derived cells: distinguishing properties of mesenchymal stem cells in humans. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:843-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura H, Muneta T, Nimura A, et al. Comparison of rat mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, synovium, periosteum, adipose tissue, and muscle. Cell Tissue Res 2007;327:449-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morito T, Muneta T, Hara K, et al. Synovial fluid-derived mesenchymal stem cells increase after intra-articular ligament injury in humans. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1137-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oe K, Kushida T, Okamoto N, et al. New strategies for anterior cruciate ligament partial rupture using bone marrow transplantation in rats. Stem Cells Dev 2011;20:671-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu H, Fan H, Toh SL, et al. A comparison of rabbit mesenchymal stem cells and anterior cruciate ligament fibroblasts responses on combined silk scaffolds. Biomaterials 2008;29:1443-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Figueroa D, Espinosa M, Calvo R, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using mesenchymal stem cells and collagen type I scaffold in a rabbit model. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014;22:1196-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Proffen BL, Vavken P, Haslauer CM, et al. Addition of autologous mesenchymal stem cells to whole blood for bioenhanced ACL repair has no benefit in the porcine model. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:320-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim JK, Hui J, Li L, et al. Enhancement of tendon graft osteointegration using mesenchymal stem cells in a rabbit model of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2004;20:899-910. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ouyang HW, Goh JC, Lee EH. Use of bone marrow stromal cells for tendon graft-to-bone healing: histological and immunohistochemical studies in a rabbit model. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:321-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soon MY, Hassan A, Hui JH, et al. An analysis of soft tissue allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in a rabbit model: a short-term study of the use of mesenchymal stem cells to enhance tendon osteointegration. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:962-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kanazawa T, Soejima T, Noguchi K, et al. Tendon-to-bone healing using autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in ACL reconstruction without a tibial bone tunnel-A histological study. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2014;4:201-6. [PubMed]

- Mifune Y, Matsumoto T, Ota S, et al. Therapeutic potential of anterior cruciate ligamentderived stem cells for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Cell Transplant 2012;21:1651-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li F, Jia H, Yu C. ACL reconstruction in a rabbit model using irradiated Achilles allograft seeded with mesenchymal stem cells or PDGF-B gene-transfected mesenchymal stem cells. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15:1219-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakamura N, Shino K, Natsuume T, et al. Early biological effect of in vivo gene transfer of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-B into healing patellar ligament. Gene Ther 1998;5:1165-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Centeno CJ, Pitts J, Al-Sayegh H, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament tears treated with percutaneous injection of autologous bone marrow nucleated cells: a case series. J Pain Res 2015;8:437-47. [PubMed]

- Steadman JR, Cameron-Donaldson ML, Briggs KK, et al. A minimally invasive technique (“healing response”) to treat proximal ACL injuries in skeletally immature athletes. J Knee Surg 2006;19:8-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steadman JR, Matheny LM, Briggs KK, et al. Outcomes following healing response in older, active patients: a primary anterior cruciate ligament repair technique. J Knee Surg 2012;25:255-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gobbi A, Bathan L, Boldrini L. Primary repair combined with bone marrow stimulation in acute anterior cruciate ligament lesions: results in a group of athletes. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:571-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gobbi A, Karnatzikos G, Sankineani SR, et al. Biological Augmentation of ACL Refixation in Partial Lesions in a Group of Athletes: Results at the 5-Year Follow-up. Tech Orthop 2013;28:180-4. [Crossref]

- Xie J, Wang C, Huang DY, et al. TGF-beta1 induces the different expressions of lysyl oxidases and matrix metalloproteinases in anterior cruciate ligament and medial collateral ligament fibroblasts after mechanical injury. J Biomech 2013;46:890-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi D, Kurosaka M, Yoshiya S, et al. Effect of basic fibroblast growth factor on the healing of defects in the canine anterior cruciate ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1997;5:189-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Madry H, Kohn D, Cucchiarini M. Direct FGF-2 gene transfer via recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors stimulates cell proliferation, collagen production, and the repair of experimental lesions in the human ACL. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:194-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takayama K, Kawakami Y, Mifune Y, et al. The effect of blocking angiogenesis on anterior cruciate ligament healing following stem cell transplantation. Biomaterials 2015;60:9-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marui T, Niyibizi C, Georgescu HI, et al. Effect of growth factors on matrix synthesis by ligament fibroblasts. J Orthop Res 1997;15:18-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray MM, Palmer M, Abreu E, et al. Platelet-rich plasma alone is not sufficient to enhance suture repair of the ACL in skeletally immature animals: an in vivo study. J Orthop Res 2009;27:639-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng M, Johnson VM, Murray MM. Effects of age and platelet-rich plasma on ACL cell viability and collagen gene expression. J Orthop Res 2012;30:79-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seijas R, Ares O, Cusco X, et al. Partial anterior cruciate ligament tears treated with intraligamentary plasma rich in growth factors. World J Orthop 2014;5:373-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fleming BC, Magarian EM, Harrison SL, et al. Collagen scaffold supplementation does not improve the functional properties of the repaired anterior cruciate ligament. J Orthop Res 2010;28:703-9. [PubMed]

- Vavken P, Fleming BC, Mastrangelo AN, et al. Biomechanical outcomes after bioenhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction are equal in a porcine model. Arthroscopy 2012;28:672-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray MM, Flutie BM, Kalish LA, et al. The Bridge-Enhanced Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair (BEAR) Procedure: An Early Feasibility Cohort Study. Orthop J Sports Med 2016;4:2325967116672176 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pereira H, Frias AM, Oliveira JM, et al. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine strategies in meniscus lesions. Arthroscopy 2011;27:1706-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Daniels AU, Andriano KP, Smutz WP, et al. Evaluation of absorbable poly(ortho esters) for use in surgical implants. J Appl Biomater 1994;5:51-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Elst M, Klein CP, de Blieck-Hogervorst JM, et al. Bone tissue response to biodegradable polymers used for intra medullary fracture fixation: a long-term in vivo study in sheep femora. Biomaterials 1999;20:121-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang C, Hillas PJ, Baez JA, et al. The application of recombinant human collagen in tissue engineering. BioDrugs 2004;18:103-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin MJ, Muotri A, Gage F, et al. Human embryonic stem cells express an immunogenic nonhuman sialic acid. Nat Med 2005;11:228-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koizumi K, Ebina K, Hart DA, et al. Synovial mesenchymal stem cells from osteo-or rheumatoid arthritis joints exhibit good potential for cartilage repair using as caffold-free tissue engineering approach. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016;24:1413-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shimomura K, Moriguchi Y, Ando W, et al. Osteochondral repair using a scaffold-free tissue-engineered construct derived from synovial mesenchymal stem cells and a hydroxyapatite-based artificial bone. Tissue Eng Part A 2014;20:2291-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujie H, Nakamura N. Frictional properties of articular cartilage-like tissues repaired with a mesenchymal stem cell-based tissue engineered construct. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2013;2013:401-4. [PubMed]

- Ando W, Tateishi K, Katakai D, et al. In vitro generation of a scaffold-free tissue-engineered construct (TEC) derived from human synovial mesenchymal stem cells: biological and mechanical properties and further chondrogenic potential. Tissue Eng Part A 2008;14:2041-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moriguchi Y, Tateishi K, Ando W, et al. Repair of meniscal lesions using a scaffold-free tissue-engineered construct derived from allogenic synovial MSCs in a miniature swine model. Biomaterials 2013;34:2185-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shimomura K, Ando W, Tateishi K, et al. The influence of skeletal maturity on allogenic synovial mesenchymal stem cellbased repair of cartilage in a large animal model. Biomaterials 2010;31:8004-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ando W, Tateishi K, Hart DA, et al. Cartilage repair using an in vitro generated scaffold-free tissue-engineered construct derived from porcine synovial mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials 2007;28:5462-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

李亘

2013年获得中南大学临床医学本科学位,2016年获得上海交通大学外科学专业硕士学位。2019年取得同济大学外科学(学术型)博士学位。参与国家级课题2项,省部级课题4项、院级课题1项。成果以第一、共同第一作者发表于在Science Advances、Chemical Engineering Journal、Molecules and Cells、Bone、Bone & Joint Research等期刊杂志。此外,参加了大量临床实践学习,熟练掌握创伤骨科门急诊常见疾病的诊治。博士期间分别获得美国德州大学休斯顿健康科学中心骨科及MD Anderson肿瘤中心访学邀请,并获得同济大学短期访学奖励基金资助资格。(更新时间:2021/9/13)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Uchida R, Horibe S, Nakamura N. Stem cell-based therapy in anterior cruciate ligament repair. Ann Joint 2017;2:76.