犬骨肉瘤:人类和犬类研究的交叉点

引言

骨肉瘤(Osteosarcoma,OSA)是儿童最常见的恶性骨肿瘤,10-20岁[1,2]是发病率的高峰。过去几十年,尽管已有大量的临床和患病机制研究以寻找新的药物靶点,但骨肉瘤的治疗和结局基本保持不变,对于局灶性骨肉瘤而言,患者5年无事件生存率(event-free survival,EFS)为60%~70%[1-3]。这些研究中有许多利用了细胞系,过度利用了不能反映患者原始疾病的原发肿瘤,或者说原位小鼠模型可能无法准确再现人类疾病[1,4]。现在人们热衷于用自然发生模型来比较肿瘤学和评估疾病。而对于骨肉瘤,狗提供了一个与人类疾病类似的自然发生疾病的经典模型。

犬骨肉瘤

骨肉瘤是狗中最常见的原发性骨肿瘤,并且主要发生在老年患犬上,在大多数研究中,患犬的中位/平均年龄为>8岁[5-8]。然而,人们已经意识到犬骨肉瘤的一个双峰现象,研究表明犬骨肉瘤的第二个患病高峰为三岁以下的幼犬。犬骨肉瘤中,大型犬比例较高,诸如在大丹犬、罗威纳犬、金毛寻回犬、拉布拉多猎犬和德国牧羊犬中经常被诊断出骨肉瘤[7-10]。大多数犬骨肉瘤病例发生在四肢骨[11],尽管中轴骨,如颅骨、下颌骨、上颌骨、颅外扁平骨和不规则骨(如椎体、肋骨、胸骨、肩胛骨或骨盆)中经常也有报道[12-15];此外,在一些伴侣动物的报告中也记录有骨外骨肉瘤[16]。虽然小型犬发生骨肉瘤的可能性较低,但它们比大型犬更容易发生中轴骨骨肉瘤[17]。

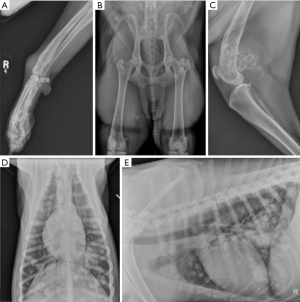

骨肉瘤具有特征性的影像学表现:犬的四肢骨肉瘤通常发生在干骺端区域,具有溶骨性和成骨性混合的影像学表现(图1)。最常见的肿瘤部位是桡骨远端和肱骨近端,但四肢其他部位的骨肉瘤也并不少见。常规分期评估包括三维胸部影像学检查以评估是否存在肺转移灶(图1)。与人类骨肉瘤类似[1],所有诊断为四肢骨肉瘤的犬中几乎都存在微转移灶,但在初次确诊骨肉瘤时,大的肺转移并不常见。在初次确诊骨肉瘤时,肺转移和骨转移的概率大致相同,其他部位的转移也有可能。腹部超声也可用于检查骨肉瘤转移[5],特别是对于伴有骨盆肢体转移、淋巴结肿大或非典型表现/临床结果的病例。同样,当查体或影像学检查发现淋巴结肿大时,应进行淋巴结活检。

在人类骨肉瘤中,分期研究识别出大约15%~20%的患者存在转移灶[1],这预示着患者预后不良[18,19]。同样地,大约10%的患犬在首次诊断骨肉瘤时会有影像学可识别的转移。然而,这个比例低估了骨肉瘤在患犬上的总体转移潜力,因为超过90%的患犬在原发病灶治疗过程中会死于肺转移[20-22]。CT被越来越多地用于评估患犬是否存在肺部转移灶[23]。尽管传统的高质量X线片能够检测到大约7-9 mm大小的肺转移灶,但据报道,CT具有能检测出1 mm大小肺转移灶的灵敏度。尽管CT提高了肺转移灶的检出率,但较小的肺转移灶与患犬生存时间的临床相关性尚不确定。

可以通过细针穿刺或骨组织活检对骨肉瘤进行细胞学诊断或组织学诊断。在一项评估使用超声引导的研究中,89%的患犬获得了诊断样本[24]。细胞学检查显示为肉瘤的诊断样本,具有较高的敏感性(97%)和特异性(100%)[24]。由于影像学上的特征性改变,我们很少对犬类中疑似骨肉瘤的病变进行治疗前活检。

目前,针对犬类骨肉瘤,推荐的治疗方法是通过手术或放疗和全身化疗对肿瘤进行积极的局部控制。下面是对现有治疗方法的回顾。此外,为了造福犬类与人类患者,新的创新疗法也正在研究中。

单纯接受截肢治疗的四肢骨肉瘤患犬,其中位生存时间(MST)小于6个月[20,21],1年和2年生存率分别为11.5%和2%[21]。截肢后进行化疗可显著改善预后,中位生存时间较单纯截肢延长2倍[25]。更长的生存时间则与骨膜骨肉瘤或骨旁骨肉瘤、身材矮小以及患犬在保肢手术后是否发生手术部位感染有关[8,26,27]。不良预后信号包括血清ALP升高、犬患骨肉瘤时不足5岁、首次确诊时存在转移性病灶(骨、淋巴结或肺)、肿瘤坏死率增加、肿瘤位于肱骨近端、高级别骨肉瘤和更大的肿瘤体积[8,28-35]。

在一项评估犬骨肉瘤组织学评分系统的研究中,根据基质的类型(类骨质、软骨和纤维组织)记录了9种不同的亚型。在超过50%的样本中,犬骨肉瘤以成骨细胞亚型为主。此外,犬骨肉瘤中的血管侵袭也是常见的,在该研究中,超过70%的原发骨肉瘤均出现这种现象[33]。该研究中的大多数骨肉瘤样本显示了侵袭性肿瘤的预期特征,如极其严重的细胞多形性,数量不等的有丝分裂和坏死[33]。

分子相似性

犬类和人类骨肉瘤临床表现的相似性强调了进行遗传评估以比较这两种疾病的重要性。由于犬的临床病程进展较快,如果确定了基因的相似性,就有可能利用犬的基因图谱来帮助寻找治疗或预后靶点。一些研究已经发现了骨肉瘤样本中出现的基因改变,犬和人类之间存在一些共同点。然而,利用这些相似性以改进人类骨肉瘤的诊断,提高预后,仍然是非常困难的。

在一项比较犬类和儿童骨肉瘤的研究中,将这些物种的基因标记聚集在一起后,无法进行区分[36]。在另一项对人类和犬类样本进行比较的研究表明,来自犬类骨肉瘤样本的数据可能有助于对人类骨肉瘤进行分子亚型的分类,这反过来可能具有临床价值[37]。最近,在一个不同品种的犬队列中评估了与骨肉瘤发生和发展相关的遗传风险因素,这是用犬来构建人类骨肉瘤模型的第一步[38]。在该研究中,发现有33个基因组区域与骨肉瘤相关,并确定了几个潜在的致病基因和通路[38]。

最近进行了转录组分析,试图比较人类、小鼠和犬类骨肉瘤细胞系[39]。有趣的是,犬和小鼠骨肉瘤样本都与人类骨肉瘤样本相关,但这种相关性未见于其他非骨肉瘤的肿瘤[39]。这类发现为进一步研究犬类和人类骨肉瘤的方式打开了新的大门,相互都能获益。

许多不同的肿瘤抑制通路和原癌基因正在犬骨肉瘤中被研究,对这些研究的全面回顾超出了本文的范畴;鼓励读者去研究专门针对这一主题的文章[22,40]。当对犬类和人类骨肉瘤进行比较时,一种参与肿瘤抑制通路的特殊蛋白质,即TP53,显示了其潜力。P53蛋白是细胞复制的一个重要调节子,P53的突变导致肿瘤细胞复制能力的增强[41]。已注意到TP53基因突变在犬类骨肉瘤中很常见[34],而且犬类和人类骨肉瘤之间似乎存在强烈的同源性[42]。此外,骨肉瘤患者和骨肉瘤患犬似乎有相似概率的p53突变[40]。

治疗

目前治疗人类骨肉瘤的方案依赖于新辅助化疗,以及后续的手术切除和术后辅助化疗。广为接受的化疗方案包括甲氨蝶呤、阿霉素和顺铂,术前2个周期和术后4个周期。手术切除的目的是获得无瘤切缘,同时尽可能保留更多的肢体功能,通常可以采用保肢方法。切除肿瘤标本中的坏死率通常被认为是预后的主要指标。不幸的是,如EURAMOS-1研究所示,将改进的术后化疗方案用以术前新辅助化疗反应不佳的患者,但并未改善他们的生存结果[1,43]。

手术治疗

与人类骨肉瘤的手术治疗相反,截肢被认为是治疗犬类四肢骨肉瘤的金标准手术方案[27]。做出截肢手术的决定对患犬主人来说通常是困难的;然而,患犬通常从手术中恢复得很好,有良好的行走能力,主人也很满意。位于前肢的肿瘤一般通过前肢截肢术来治疗。大多数外科医生倾向于采用包括切除肩胛骨在内的前肢截肢术,因为手术过程简单,肿瘤周围有广泛的切缘,而且切除肩胛骨后可以改善外观,因为肩胛骨上的肌肉萎缩后会很难看。肩胛骨肿瘤或尺骨肿瘤可以通过部分切除术来治疗[14,44];并且,我们总是推荐用更先进的影像学检查(即CT)来评估肿瘤的范围。可能需要额外的固定措施以改善功能,但大多数患犬对这些手术耐受良好。

骨盆肿瘤最常见的治疗方法是髋股关节分离术;这种手术技术通常比股骨中段截肢术更受欢迎,因为它美观、技术简单,而且手术切缘更广泛。股骨近端肿瘤除了截肢术或半骨盆切除术外,还可以通过en bloc髋臼全切术来治疗。骨盆肿瘤也可以通过部分或完全半骨盆切除术进行治疗[45]。在患犬中,半骨盆切除术连同截肢术的耐受性与单纯截肢术相似。

截肢术后的恢复通常很快,大多数患犬在术后几天内就能行走。围手术期镇痛是必不可少的,可以通过伤口浸透导管或全身用药来实现。这些手术的并发症包括血肿形成,以及不太常见的伤口裂开、出血和感染。

对犬四肢骨肉瘤的保肢手术进行了描述,但适当的病例选择和客户教育是至关重要的。一般而言,保肢手术适用于患犬因骨科或神经系统合并症而无法忍受截肢,或者患犬主人拒绝截肢的情况。已经为犬类开发了几种保肢技术,但目前,这些保肢手术的主要应用部位是桡骨远端,因为其他部位在保肢术后评估功能结果时,效果不甚理想;患犬往往能很好地耐受腕关节融合术,可能是因为这种手术在桡骨骨肉瘤病例中的成功率很高[27,46,47]。已注意到犬保肢手术有明显的并发症,主要包括早期感染、内植物失败和局部复发[48]。在一些研究中,感染率已超过70%,这种高感染率可能是由于各种因素造成的,如血供受损、软组织覆盖率低、内植物的使用和随后的化疗[48]。

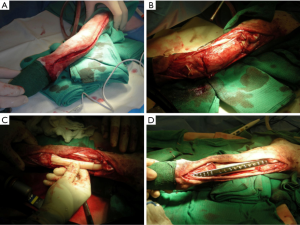

在20世纪80年代末,保肢手术首次被证明对患有骨肉瘤的犬是可行的[46]。最早的犬类保肢技术是在切除肿瘤后进行同种异体皮质骨移植[27]。在这些病例中,肿瘤和邻近的组织被en bloc切除,并利用预制的同种异体皮质骨移植物来填补肿瘤切除后留下的缺损。一个保肢接骨板将同种异体皮质骨移植物连接到患犬近端桡骨和掌骨上,从而完成腕关节融合术(图2)。

由于骨采集和骨库维护方面的挑战,人们开发了一种内固定假体。最早的内固定假体设计是由316L手术钢制成,预制的长度为122 mm,包括两个机械加工孔。专门设计的保肢接骨板与内固定假体一起使用,接骨板有24个孔;近端孔可容纳3.5或4.5 mm的桡骨皮质骨螺钉,以及2.7或3.5 mm的掌骨皮质骨螺钉。

有研究比较了与同种异体皮质骨移植物和内固定假体相关的生物力学和临床结果[27,49]。生物力学比较是以尸体研究的形式进行的,在犬前肢上用同种异体皮质骨移植或钢制内固定假体进行保肢手术;作者还评估了尺骨的保肢手术在生物力学上是否重要[49]。用内固定假体重建的肢体在生物力学上优于用同种异体皮质骨移植重建的肢体,然而,两组之间在强度或内固定失败所需能量方面没有明显差异[49]。前臂稳定不需要尺骨,这使得外科医生可以更积极地尝试实现广泛的外科切缘,因为尺骨可以被切除[49]。在临床研究中,同种异体皮质骨移植组和假体组中都有40%的犬发生内固定失败;但是两组的内固定失败方式不同[27]。在同种异体皮质骨移植组,螺钉松动或断裂出现在桡腕骨或掌骨。在内固定假体组,螺钉松动或断裂发生在桡骨近端。总的来说,75%患犬的肢体功能被确定为良好至优秀,两组之间没有显著差异[27]。在上述研究结果出来后,第二代钢制内固定假体被开发出来,目的是解决第一代内固定假体上发现的一些问题[48]。然而,在最近的一项研究中,当对两种内固定假体进行比较时,在并发症严重程度、并发症发生率或发生时间方面没有发现明显的差异[48]。

其他犬保肢技术也尝试利用自体骨。有几项研究描述了这样一种技术,称为尺骨翻转移位术[50,51]。在这种技术中,肿瘤累及的桡骨部分被切除。进行两个尺骨截骨术,从而形成一个与所切除的桡骨部分长度大致相同的尺骨段。目的是保留尾端的骨间动脉和静脉,以及一些肌肉附着物,以改善尺骨在新部位的接纳情况。尺骨移植物被卷进桡骨肿瘤所切除的位置,在残存的桡骨和腕骨之间。然后放置一个动态加压板,范围从剩余的桡骨段到第四掌骨,两个螺钉也被置入尺骨移植物[51]。关于该技术的最初研究表明,在三只患犬中,移植骨存活良好,患肢术后具有良好至优秀的功能。在最近的一项研究中,描述了26只患犬的结局,在那些已知结果的肢体中,移植骨的存活率相对较高,为85%[50]。然而,与其他保肢技术类似,尺骨翻转移位术的并发症率似乎很高[50]。还有人描述了一种类似的技术,在这种技术中,前肢被横向切除,使尺骨能够填补切除桡骨骨肉瘤后留下的缺损[52]。这种手术的目的是将前肢横向切除,使桡腕骨的近端表面与尺骨远端接触。然后在剩余桡骨的头侧放置骨板,并延伸到第三掌骨的背侧,以及从尺骨的外侧到第四掌骨的头侧[52]。桡骨切除量的中位数是54%,有一只患犬接受了94%的桡骨切除[52]。

其他已经使用的技术包括牵引成骨术[53]和经血管化[51]、放射[54]和巴氏灭菌[55]的自体骨移植。最近,有研究报道了3D打印的内固定假体[56,57]。早期结果前景良好,但还需要进一步研究。在一只患犬身上,研究了一个3D打印的支架。在这个案例中,没有发生与支架或手术有关的并发症,并注意到肢体功能和生活质量有明显改善[56]。

在一些研究中,手术部位感染(surgical-site infection,SSI)的发展已经被报道为延长了接受保肢手术的患犬的生存时间[26,27,58]。这由Thrall等人首次报道,其中与异体移植物相关的感染病例有更好的局部控制率和更长的生存时间[59]。2005年,Lascelles等人报道了47只接受保肢手术和辅助化疗的患犬。在这47患犬中,32只(68%)发生了SSI,这些患犬比没有发生SSI的患犬有生存优势[26]。此外,发生手术部位感染的患犬在首次诊断时就发现转移灶的概率会降低一半[26]。在一项比较接受同种异体皮质骨移植保肢和接受钢制内固定假体保肢的患犬的研究中,证明发生感染患犬(685天)的中位生存时间长于没有发生感染的患犬(289天)。然而,两组之间的总体感染率没有显著差异,这是一个有趣的发现,因为人们认为,由于缺乏异体诱导的异物反应,钢制内固定假体病例不太可能在术后发生感染[27]。在最近的一项研究中,对组织病理学诊断为骨肉瘤后存活超过一年的患犬进行评估,发现了与上述研究类似的结果[58]。该研究中发生SSI的20只患犬在1年后的生存时间明显延长。SSI组的患犬1年后的中位生存期为180天(范围为25-1899天),而没有发生SSI的患犬的中位生存期为28天(范围为8-282天)[58]。最近在一组接受截肢手术的患犬中评估了SSI对中位生存期的潜在影响[60]。在该研究队列中,有SSI的患犬与没有SSI的患犬相比,无病生存期和中位生存期都没有受到影响[60]。有趣的是,一些人类骨肉瘤研究也报道了类似的发现,即有SSI的患者在保肢重建术后生存率增加[61,62]。SSI在改善生存率方面的作用使人们猜测有一种自身免疫治疗的机制,并为这种疾病的免疫治疗研究的持续努力增加了砝码,研究成果有可能转化,从而造福犬类和人类患者[63]。

化疗

在过去25年里,主要影响骨肉瘤患犬预后的是在没有检测到转移灶的情况下加入辅助化疗[8,64]。然而,犬类的化疗给药方式与人类患者不同,骨肉瘤患犬的化疗一般都是按照一定的方式和时间表给药,从而将化疗引起的并发症概率降到最低。正因为如此,骨肉瘤患犬的化疗通常耐受性良好,毒性最小[21]。此外,这些化疗药物如顺铂和甲氨蝶呤通常用于人类骨肉瘤患者,并不是伴侣动物典型骨肉瘤化疗方案的一部分。高剂量甲氨蝶呤尚未在犬身上进行充分的研究,因为其生产紧张,成本高。虽然顺铂具有很高的毒性,但它在人类骨肉瘤中作用似乎更有优势,在患犬的生存上并没有表现出比卡铂更强的优势。

总的来说,铂类药物单药或卡铂与阿霉素交替的化疗方案是最频繁被研究的[20,64-69]。多项研究表明,交替治疗方案并没有优于单药治疗方案[64,68]。一些研究试图评估单用卡铂方案是否与卡铂和阿霉素交替方案同样有效[6]。在第一项研究中,比较了5种方案:卡铂给药4或6个周期,阿霉素每14或21天给药持续5个周期,卡铂和阿霉素交替给药[6]。对这些不同方案进行统计比较后,没有一种方案显示能够显著降低转移或死亡的风险;然而,与其余方案相比,犬类单用6个疗程卡铂发生不良反应事件的比例较低[6]。最近的一项研究比较了使用六个疗程卡铂与每次交替使用三个疗程卡铂和三个疗程阿霉素的方案[7]。与交替使用卡铂和阿霉素的患犬相比(134天),单用卡铂的患犬(425天)无病生存期明显更长[7]。

虽然在对没有发现转移灶的骨肉瘤患犬的治疗方案中加入化疗似乎延长了它们的中位生存时间,但化疗对存在转移灶骨肉瘤治疗的影响尚不清楚。用于骨肉瘤患犬的传统化疗药物已经被证明大多是无效的[70]。最近,异环磷酰胺被用于一组伴有明显转移灶的骨肉瘤患犬[71]。虽然只有17/19只患犬可以进行反应评估,但结果令人失望:仅有11.8%的应答率[71]。该药物的耐受性良好,但一个疗程后的中位生存时间仅为95天[71]。类似地,在存在肉眼可见的肺转移灶患犬中使用小分子受体酪氨酸激酶抑制剂(托西尼布),应答反应非常小[72]。

雾化吸入化疗也被认为是一种治疗犬肺转移灶的方式,因为它有可能增加药物的局部浓度并降低全身毒性[73,74]。通过带有雾化器的压缩机对20只骨肉瘤患犬进行吉西他滨雾化吸入治疗。由于副作用很小,用药的耐受性良好;特别是,没有一只患犬的动脉血气和肺泡动脉梯度与基线相比有变化,也没有胃肠道毒性报告[73]。当生活质量被认为是严重下降或无法接受时,会对患犬进行人道主义安乐死,并取其肺脏切片进行评估。组织学上,吉西他滨引起的气道和肺毒性反应很轻微;然而,在所有患犬的肿瘤内都发现了坏死,这在今后为犬类的进一步研究中打开了大门[73]。在另一项研究中,28只患犬中有10只被诊断为骨肉瘤,患犬吸入阿霉素和(或)紫杉醇[74]接受治疗。应答率仅为25%,但同样地,没有发生全身毒性反应。紫杉醇在肺的局部也能耐受,但大约50%的患犬服用阿霉素后出现间歇性的、无痰干咳[74]。

免疫疗法正在改变多种人类癌症的治疗前景,兽医病例中也正在探索多种模式。当思考存在微转移灶的骨肉瘤患犬的治疗时,活化巨噬细胞和单核细胞是一个有吸引力的选择[75,76]。可以用被脂质体包裹的免疫调节剂活化巨噬细胞和单核细胞,以靶向破坏肿瘤细胞[75]。在几项关于犬骨肉瘤的研究中,已在探究脂质体包裹的胞壁酰三肽-磷脂酰乙醇胺(liposome-encapsulated muramyl tripeptide-phosphatidylethanolamine,L-MTP-PE)这类药物[75-78]。当L-MTP-PE通过静脉注射给患犬时,其具有良好的耐受性,主要副作用仅是体温的轻度升高[75,76]。最早使用L-MTP-PE治疗骨肉瘤患犬的研究中,采用随机、双盲法。这些患犬首先接受截肢手术,然后被随机分为两组,一组接受L-MTP-PE治疗,另一组接受安慰剂治疗[76]。接受L-MTP-PE治疗的患犬存活时间显著延长(222天),而接受安慰剂治疗的患犬存活时间仅为77天[76]。值得注意的是,在L-MTP-PE组中,4只患犬术后存活时间超过1年,且没有发生转移[76]。

随访研究开始评估接受L-MTP-PE治疗的患犬中化疗的影响[75,78]。在第一项研究中,评估了对截肢后进行四个疗程顺铂治疗的原发性肿瘤患犬增加L-MTP-PE的效果[75]。完成化疗后,患犬被随机分为安慰剂组和L-MTP-PE组。与安慰剂组相比,L-MTP-PE组患犬的中位无病生存时间和中位生存时间明显更长[75]。在两项随机、双盲临床试验发表1年后,接受L-MTP PE治疗(在截肢和顺铂治疗后)的患犬再次显示比安慰剂组患犬存活时间更长[78]。然而,同时使用顺铂与L-MTP-PE治疗的患犬并没有表现出生存优势[78]。在人类骨肉瘤中也进行了L-MTP-PE研究,据报道,局灶性和转移性患者的EFS均有改善[3,79,80]。研究结果仍然存在一定的争议,并且尽管L-MTP-PE(mifamurtide)在欧洲获得了上市批准,但却被美国FDA否决[1]。

白细胞介素2(Interleukin 2,IL-2)具有调节免疫应答以靶向治疗癌细胞的潜力,因此人们正在研究IL-2的治疗用途[25,81,82]。由于IL-2较窄的治疗谱并有潜在的副作用,雾化使用IL-2是一个有吸引力的研究选择。使用雾化IL-2的免疫治疗方法在治疗肺转移性病变方面具有特殊的潜力,因为可以增加药物的局部浓度,并能将全身副作用理想地降到最低。有一个病例系列研究描述了应用雾化的IL-2脂质体治疗一组被诊断为肺转移瘤或原发性肺癌的患犬[83]。在该组中,4只骨肉瘤肺转移的患犬中有2只肺转移灶完全消退,且消退时间分别稳定在12个月以上和20个月以上[83]。此外,IL-2治疗相关的毒性被认为是最小的[83]。IL-2作为NK细胞的兴奋剂以治疗肺转移,也是人类骨肉瘤的研究目标。这已经在小鼠模型的体内研究中进行了评估,证明了NK细胞对肺结节的杀伤作用增强[84]。

2016年发表的一项具有里程碑意义的研究描述了高度减毒、表达嵌合人类HER2/neu融合蛋白(ADXS31-164)的重组单核增生李斯特菌对已经接受截肢或保肢手术加辅助化疗的骨肉瘤患犬的治疗[85]。该研究的目的是“确定ADXS31-164的安全性及其在截肢和卡铂辅助化疗后的自发性骨肉瘤患犬体内产生HER2/neo特异性免疫的能力”,并“确定ADXS31-164在最小残留疾病的情况下应用是否能够预防转移并延长总生存期[85]。接受截肢或保肢手术后也接受四个疗程卡铂化疗的患犬被纳入研究。药物相关的毒性反应被认为是短暂的和低级别的。本研究表明,在接受ADXS31-164治疗的6个月内,15/18只患犬产生了针对HER2/neu的胞内结构域的抗原特异性IFNY应答反应[85]。令人印象深刻的是,接受ADXS31-164治疗的患犬1年、2年和3年生存率分别为77.8%、67%和56%[85]。更多的工作正在进行中,以进一步推动这一有前景的研究。

放疗

不同形式的放疗可用于治疗犬类骨肉瘤病例中的局部病灶。由于费用、对邻近组织的副作用以及与标准手术治疗相比缺乏益处[86],犬类通常不进行治疗目的的全疗程放疗。在无法进行手术或主人不选择积极治疗的情况下,姑息性放疗也可用于缓解疼痛。一般来说,姑息性放疗包括将几次大剂量放疗分为2-4个部分进行[87]。减轻炎症反应、减缓骨溶解、缩小肿瘤体积都是姑息性放疗的益处。超过50%的患者对治疗有反应,疼痛在1-2周内缓解,改善持续约2-3个月[87]

在一些研究[88-91]中,立体定向放射外科(SRS)或立体定向放射治疗(SRT)已经被应用于治疗犬四肢骨肉瘤,并且最近同样被用于治疗椎体骨肉瘤[92]。犬SRS/SRT后出现骨折是一个主要问题,因此筛选适合此方法的患者是至关重要的。肿瘤累及的骨骼区域大小已被证明是决定放疗后是否可能骨折的一个重要影响因素;有软骨下骨累及的犬中位骨折时间为4.2个月,而没有软骨下骨累及的犬中位骨折时间为16.3个月[91]。

由于考虑到骨肉瘤继发的病理性骨折和RT复合治疗,在一项研究中,在SRT治疗的同时进行了固定[88]。在该组队列中,SRT联合应用骨板或交锁螺钉进行固定,并发症发生率异常高;据报道,大约90%的患犬发生严重并发症(如感染、骨折)[88]。在另一项研究中,6只在接受SRS之前或之后发生病理性骨折的患犬接受了内固定治疗[89]。感染和内固定失败率很高,但当植入物固定,感染不明显时,肢体功能被认为是良好[58]。

有三项研究联合了动脉内化疗和放疗治疗犬类骨肉瘤[93-95]。在四肢骨肉瘤的研究中,有主人的患犬接受了动脉内顺铂治疗(2个疗程,间隔21天),并且其中大多数患犬同时接受了放疗[95]。这些患犬的中位生存时间为9.3个月。作者指出,这些患犬的生存时间比仅截肢患犬的预期生存时间更长,这表明动脉内化疗有助于患犬生存[95]。肿瘤坏死>75%的患犬在1年的复发率(15%)显著低于肿瘤坏死<75%患犬(65%)[95]。另一项研究比较了犬类骨肉瘤的不同治疗方法,包括单独动脉内化疗和动脉内化疗联合放疗,这些治疗方法的肿瘤坏死率分别为49.1%和83.7%[94]。该研究表明,相对于仅采用42.2 Gy的放射剂量进行放疗,使用28.1 Gy的放射剂量联合动脉内化疗可导致80%的肿瘤坏死[94]。人类患者中有趣的是,在使用甲氨蝶呤、顺铂和阿霉素的标准新辅助化疗方案后,切除标本中建立的肿瘤坏死率目标为>90%。另一项犬类研究证明,接受动脉内顺铂化疗联合放疗替代截肢或保肢手术的犬的中位生存时间为6.7个月[93]。动脉内化疗也已与保肢手术联合使用[46,57]。

总结

骨肉瘤在犬身上是自然发生的,其在临床病程、遗传学和治疗策略上都与人类疾病有惊人的相似之处。虽然在这些物种中对比研究骨肉瘤的好处是显而易见的,但在患犬中进行临床试验存在着固有挑战。犬被认为是宠物,在很多情况下它们被认为是家庭成员的一份子,这可能会给它们的主人在治疗决策上带来困难。因此,在研究设计过程中,必须考虑患犬的风险和潜在收益,以确保监管批准和获益累积。同样,主人的知情同意是绝对必要的。

此外,犬骨肉瘤治疗的经济负担一般落在主人身上,而且由于治疗费用,在治疗上可能存在固有的限制。然而,近年来对犬骨肉瘤管理的进步也有可能使人类受益的认识,极大地促进了开展高质量、有影响力的临床试验的机会。

当前和未来的研究可能会继续探索免疫治疗方法,包括免疫调节、过继性免疫细胞治疗以及靶向治疗耐药细胞群,如肿瘤干细胞。此外,肿瘤微环境研究对进一步了解肿瘤发生和转移具有重要意义。通过比较研究,新的目标、新的策略和新的治疗方法可以协同发展,希望能改善人类和犬类患者的结局。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aoj.2019.11.03). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Harrison DJ, Schwartz CL. Osteogenic sarcoma: systemic chemotherapy options for localized disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2017;18:24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luetke A, Meyers PA, Lewis I, et al. Osteosarcoma treatment - where do we stand? A state of the art review. Cancer Treat Rev 2014;40:523-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyers PA, Schwartz CL, Krailo M, et al. Osteosarcoma: a randomized, prospective trial of the addition of ifosfamide and/or muramyl tripeptide to cisplatin, doxorubicin, and high-dose methotrexate. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2004-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacques C, Renema N, Lezot F, et al. Small animal models for the study of bone sarcoma pathogenesis: characteristics, therapeutic interests and limitations. J Bone Oncol 2018;12:7-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sacornrattana O, Dervisis NG, McNiel EA. Abdominal ultrasonographic findings at diagnosis of osteosarcoma in dogs and association with treatment outcome. Vet Comp Oncol 2013;11:199-207. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Selmic LE, Burton JH, Thamm DH, et al. Comparison of carboplatin and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy protocols in 470 dogs after amputation for treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 2014;28:554-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skorupski KA, Uhl JM, Szivek A, et al. Carboplatin versus alternating carboplatin and doxorubicin for the adjuvant treatment of canine appendicular osteosarcoma: a randomized, phase III trial. Vet Comp Oncol 2016;14:81-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bergman PJ, MacEwen EG, Kurzman ID, et al. Amputation and carboplatin for treatment of dogs with osteosarcoma: 48 cases (1991 to 1993). J Vet Intern Med 1996;10:76-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Story AL, Boston SE, Kilkenny JJ, et al. Evaluation of weight change during carboplatin therapy in dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 2017;31:1159-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sapierzyński R, Czopowicz M. The animal-dependent risk factors in canine osteosarcomas. Pol J Vet Sci 2017;20:293-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fenger JM, London CA, Kisseberth WC. Canine osteosarcoma: a naturally occurring disease to inform pediatric oncology. ILAR J 2014;55:69-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gold R, Oliveira F, Pool R. Zygomatic arch parosteal osteosarcoma in dogs and a cat. Vet Pathol 2019;56:274-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kruse MA, Holmes ES, Balko JA, et al. Evaluation of clinical and histopathologic prognostic factors for survival in canine osteosarcoma of the extracranial flat and irregular bones. Vet Pathol 2013;50:704-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montinaro V, Boston SE, Buracco P, et al. Clinical outcome of 42 dogs with scapular tumors treated by scapulectomy: a Veterinary Society of Surgical Oncology (VSSO) retrospective study (1995-2010). Vet Surg 2013;42:943-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Selmic LE, Lafferty MH, Kamstock DA, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors for osteosarcoma of the maxilla, mandible, or calvarium in dogs: 183 cases (1986-2012). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2014;245:930-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duffy D, Selmic LE, Kendall AR, et al. Outcome following treatment of soft tissue and visceral extraskeletal osteosarcoma in 33 dogs: 2008-2013. Vet Comp Oncol 2017;15:46-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rebhun RB, Kass PH, Kent MS, et al. Evaluation of optimal water fluoridation on the incidence and skeletal distribution of naturally arising osteosarcoma in pet dogs. Vet Comp Oncol 2017;15:441-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaste SC, Pratt CB, Cain AM, et al. Metastases detected at the time of diagnosis of primary pediatric extremity osteosarcoma at diagnosis: imaging features. Cancer 1999;86:1602-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyers PA, Gorlick R. Osteosarcoma. Pediatr Clin North Am 1997;44:973-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bacon NJ, Ehrhart NP, Dernell WS, et al. Use of alternating administration of carboplatin and doxorubicin in dogs with microscopic metastases after amputation for appendicular osteosarcoma: 50 cases (1999-2006). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;232:1504-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spodnick GJ, Berg J, Rand WM, et al. Prognosis for dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma treated by amputation alone: 162 cases (1978-1988). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1992;200:995-9. [PubMed]

- Varshney J, Scott MC, Largaespada DA, et al. Understanding the osteosarcoma pathobiology: A comparative oncology approach. Vet Sci 2016;3: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oblak ML, Boston SE, Woods JP, et al. Comparison of concurrent imaging modalities for staging of dogs with appendicular primary bone tumours. Vet Comp Oncol 2015;13:28-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Britt T, Clifford C, Barger A, et al. Diagnosing appendicular osteosarcoma with ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration: 36 cases. J Small Anim Pract 2007;48:145-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez CO Jr. Using canine osteosarcoma as a model to assess efficacy of novel therapies: can old dogs teach us new tricks? Adv Exp Med Biol 2014;804:237-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lascelles BD, Dernell WS, Correa MT, et al. Improved survival associated with postoperative wound infection in dogs treated with limb-salvage surgery for osteosarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12:1073-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liptak JM, Dernell WS, Ehrhart N, et al. Cortical allograft and endoprosthesis for limb-sparing surgery in dogs with distal radial osteosarcoma: a prospective clinical comparison of two different limb-sparing techniques. Vet Surg 2006;35:518-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boerman I, Selvarajah GT, Nielen M, et al. Prognostic factors in canine appendicular osteosarcoma - a meta-analysis. BMC Vet Res 2012;8:56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hillers KR, Dernell WS, Lafferty MH, et al. Incidence and prognostic importance of lymph node metastases in dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma: 228 cases (1986-2003). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005;226:1364-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ehrhart N, Dernell WS, Hoffmann WE, et al. Prognostic importance of alkaline phosphatase activity in serum from dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma: 75 cases (1990-1996). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;213:1002-6. [PubMed]

- Garzotto CK, Berg J, Hoffmann WE, et al. Prognostic significance of serum alkaline phosphatase activity in canine appendicular osteosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 2000;14:587-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coyle VJ, Rassnick KM, Borst LB, et al. Biological behaviour of canine mandibular osteosarcoma. A retrospective study of 50 cases (1999-2007). Vet Comp Oncol 2015;13:89-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kirpensteijn J, Kik M, Rutteman GR, et al. Prognostic significance of a new histologic grading system for canine osteosarcoma. Vet Pathol 2002;39:240-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kirpensteijn J, Kik M, Teske E, et al. TP53 gene mutations in canine osteosarcoma. Vet Surg 2008;37:454-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmidt AF, Nielen M, Klungel OH, et al. Prognostic factors of early metastasis and mortality in dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma after receiving surgery: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Prev Vet Med 2013;112:414-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paoloni M, Davis S, Lana S, et al. Canine tumor cross-species genomics uncovers targets linked to osteosarcoma progression. BMC Genomics 2009;10:625. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scott MC, Sarver AL, Gavin KJ, et al. Molecular subtypes of osteosarcoma identified by reducing tumor heterogeneity through an interspecies comparative approach. Bone 2011;49:356-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karlsson EK, Sigurdsson S, Ivansson E, et al. Genome-wide analyses implicate 33 loci in heritable dog osteosarcoma, including regulatory variants near CDKN2A/B. Genome Biol 2013;14:R132. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scott MC, Temiz NA, Sarver AE, et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis quantifies immune cell transcript levels, metastatic progression, and survival in osteosarcoma. Cancer Res 2018;78:326-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mueller F, Fuchs B, Kaser-Hotz B. Comparative biology of human and canine osteosarcoma. Anticancer Res 2007;27:155-64. [PubMed]

- O'Brien MG, Straw RC, Withrow SJ, et al. Resection of pulmonary metastases in canine osteosarcoma: 36 cases (1983-1992). Vet Surg 1993;22:105-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nasir L, Argyle DJ, McFarlane ST, et al. Nucleotide sequence of a highly conserved region of the canine p53 tumour suppressor gene. DNA Seq 1997;8:83-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marina NM, Smeland S, Bielack SS, et al. Comparison of MAPIE versus MAP in patients with a poor response to preoperative chemotherapy for newly diagnosed high-grade osteosarcoma (EURAMOS-1): an open-label, international, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1396-408. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sivacolundhu RK, Runge JJ, Donovan TA, et al. Ulnar osteosarcoma in dogs: 30 cases (1992-2008). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013;243:96-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bray JP, Worley DR, Henderson RA, et al. Hemipelvectomy: outcome in 84 dogs and 16 cats. A Veterinary Society of Surgical Oncology retrospective study. Vet Surg 2014;43:27-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LaRue SM, Withrow SJ, Powers BE, et al. Limb-sparing treatment for osteosarcoma in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1989;195:1734-44. [PubMed]

- Kuntz CA, Asselin TL, Dernell WS, et al. Limb salvage surgery for osteosarcoma of the proximal humerus: outcome in 17 dogs. Vet Surg 1998;27:417-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell KE, Boston SE, Kung M, et al. Outcomes of limb-sparing surgery using two generations of metal endoprosthesis in 45 dogs with distal radial osteosarcoma. A Veterinary Society of Surgical Oncology retrospective study. Vet Surg 2016;45:36-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liptak JM, Ehrhart N, Santoni BG, et al. Cortical bone graft and endoprosthesis in the distal radius of dogs: a biomechanical comparison of two different limb-sparing techniques. Vet Surg 2006;35:150-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Séguin B, O'Donnell MD, Walsh PJ, et al. Long-term outcome of dogs treated with ulnar rollover transposition for limb-sparing of distal radial osteosarcoma: 27 limbs in 26 dogs. Vet Surg 2017;46:1017-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Séguin B, Walsh PJ, Mason DR, et al. Use of an ipsilateral vascularized ulnar transposition autograft for limb-sparing surgery of the distal radius in dogs: an anatomic and clinical study. Vet Surg 2003;32:69-79. [PubMed]

- Séguin B, Walsh PJ, Ehrhart EJ, et al. Lateral manus translation for limb-sparing surgery in 18 dogs with distal radial osteosarcoma in dogs. Vet Surg 2019;48:247-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ehrhart N. Longitudinal bone transport for treatment of primary bone tumors in dogs: technique description and outcome in 9 dogs. Vet Surg 2005;34:24-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boston SE, Duerr F, Bacon N, et al. Intraoperative radiation for limb sparing of the distal aspect of the radius without transcarpal plating in five dogs. Vet Surg 2007;36:314-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morello E, Vasconi E, Martano M, et al. Pasteurized tumoral autograft and adjuvant chemotherapy for the treatment of canine distal radial osteosarcoma: 13 cases. Vet Surg 2003;32:539-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi S, Oh YI, Park KH, et al. New clinical application of three-dimensional-printed polycaprolactone/beta-tricalcium phosphate scaffold as an alternative to allograft bone for limb-sparing surgery in a dog with distal radial osteosarcoma. J Vet Med Sci 2019;81:434-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Séguin B, Pinard C, Lussier B, et al. Limb-sparing in dogs using patient-specific, 3 dimensional-printed endoprosthesis for distal radial osteosarcoma: a pilot study. Vet Comp Oncol 2020;18:92-104. [PubMed]

- Culp WT, Olea-Popelka F, Sefton J, et al. Evaluation of outcome and prognostic factors for dogs living greater than one year after diagnosis of osteosarcoma: 90 cases (1997-2008). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2014;245:1141-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thrall DE, Withrow SJ, Powers BE, et al. Radiotherapy prior to cortical allograft limb sparing in dogs with osteosarcoma: a dose response assay. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1990;18:1351-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hans EC, Pinard C, van Nimwegen SA, et al. Effect of surgical site infection on survival after limb amputation in the curative-intent treatment of canine appendicular osteosarcoma: a Veterinary Society of Surgical Oncology retrospective study. Vet Surg 2018;47:E88-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen YU, Xu SF, Xu M, et al. Postoperative infection and survival in osteosarcoma patients: Reconsideration of immunotherapy for osteosarcoma. Mol Clin Oncol 2015;3:495-500. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeys LM, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, et al. Post operative infection and increased survival in osteosarcoma patients: are they associated? Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:2887-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sottnik JL. Chronic bacterial osteomyelitis suppression of tumor growth requires innate immune responses. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2010;59:367-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phillips B, Powers BE, Dernell WS, et al. Use of single-agent carboplatin as adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy in conjunction with amputation for appendicular osteosarcoma in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2009;45:33-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berg J, Weinstein MJ, Schelling SH, et al. Treatment of dogs with osteosarcoma by administration of cisplatin after amputation or limb-sparing surgery: 22 cases (1987-1990). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1992;200:2005-8. [PubMed]

- Frimberger AE, Chan CM, Moore AS. Canine osteosarcoma treated by post-amputation sequential accelerated doxorubicin and carboplatin chemotherapy: 38 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2016;52:149-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kent MS, Strom A, London CA, et al. Alternating carboplatin and doxorubicin as adjunctive chemotherapy to amputation or limb-sparing surgery in the treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2004;18:540-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bailey D, Erb H, Williams L, et al. Carboplatin and doxorubicin combination chemotherapy for the treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma in the dog. J Vet Intern Med 2003;17:199-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Straw RC, Withrow SJ, Richter SL, et al. Amputation and cisplatin for treatment of canine osteosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 1991;5:205-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boston SE, Ehrhart NP, Dernell WS, et al. Evaluation of survival time in dogs with stage III osteosarcoma that undergo treatment: 90 cases (1985-2004). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006;228:1905-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Batschinski K, Dervisis NG, Kitchell BE. Evaluation of ifosfamide salvage therapy for metastatic canine osteosarcoma. Vet Comp Oncol 2014;12:249-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim C, Matsuyama A, Mutsaers AJ, et al. Retrospective evaluation of toceranib (Palladia) treatment for canine metastatic appendicular osteosarcoma. Can Vet J 2017;58:1059-64. [PubMed]

- Rodriguez CO Jr, Crabbs TA, Wilson DW, et al. Aerosol gemcitabine: preclinical safety and in vivo antitumor activity in osteosarcoma-bearing dogs. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2010;23:197-206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hershey AE, Kurzman ID, Forrest LJ, et al. Inhalation chemotherapy for macroscopic primary or metastatic lung tumors: proof of principle using dogs with spontaneously occurring tumors as a model. Clin Cancer Res 1999;5:2653-9. [PubMed]

- MacEwen EG, Kurzman ID, Helfand S, et al. Current studies of liposome muramyl tripeptide (CGP 19835A lipid) therapy for metastasis in spontaneous tumors: a progress review. J Drug Target 1994;2:391-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- MacEwen EG, Kurzman ID, Rosenthal RC, et al. Therapy for osteosarcoma in dogs with intravenous injection of liposome-encapsulated muramyl tripeptide. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989;81:935-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurzman ID, Cheng H, MacEwen EG. Effect of liposome-muramyl tripeptide combined with recombinant canine granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on canine monocyte activity. Cancer Biother 1994;9:113-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurzman ID, MacEwen EG, Rosenthal RC, et al. Adjuvant therapy for osteosarcoma in dogs: results of randomized clinical trials using combined liposome-encapsulated muramyl tripeptide and cisplatin. Clin Cancer Res 1995;1:1595-601. [PubMed]

- Mori K, Ando K, Heymann D. Liposomal muramyl tripeptide phosphatidyl ethanolamine: a safe and effective agent against osteosarcoma pulmonary metastases. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2008;8:151-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyers PA, Schwartz CL, Krailo MD, et al. Osteosarcoma: the addition of muramyl tripeptide to chemotherapy improves overall survival--a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:633-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khanna C, Hasz DE, Klausner JS, et al. Aerosol delivery of interleukin 2 liposomes is nontoxic and biologically effective: canine studies. Clin Cancer Res 1996;2:721-34. [PubMed]

- Khanna C, Waldrep JC, Anderson PM, et al. Nebulized interleukin 2 liposomes: aerosol characteristics and biodistribution. J Pharm Pharmacol 1997;49:960-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khanna C, Anderson PM, Hasz DE, et al. Interleukin-2 liposome inhalation therapy is safe and effective for dogs with spontaneous pulmonary metastases. Cancer 1997;79:1409-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guma SR, Lee DA, Yu L, et al. Natural killer cell therapy and aerosol interleukin-2 for the treatment of osteosarcoma lung metastasis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:618-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mason NJ, Gnanandarajah JS, Engiles JB, et al. Immunotherapy with a HER2-targeting Listeria induces HER2-specific immunity and demonstrates potential therapeutic effects in a phase I trial in canine osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:4380-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walter CU, Dernell WS, LaRue SM, et al. Curative-intent radiation therapy as a treatment modality for appendicular and axial osteosarcoma: a preliminary retrospective evaluation of 14 dogs with the disease. Vet Comp Oncol 2005;3:1-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pagano C, Boudreaux B, Shiomitsu K. Safety and toxicity of an accelerated coarsely fractionated raditiaon protocol for treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma in 14 dogs: 10 Gy x 2 fractions. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2016;57:551-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boston SE, Vinayak A, Lu X, et al. Outcome and complications in dogs with appendicular primary bone tumors treated with stereotactic radiotherapy and concurrent surgical stabilization. Vet Surg 2017;46:829-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Covey JL, Farese JP, Bacon NJ, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery and fracture fixation in 6 dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma. Vet Surg 2014;43:174-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farese JP, Milner R, Thompson MS, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for treatment of osteosarcomas involving the distal portions of the limbs in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004;225:1567-1572. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kubicek L, Vanderhart D, Wirth K, et al. Association between computed tomographic characteristics and fractures following stereotactic radiosurgery in dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2016;57:321-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swift KE, LaRue SM. Outcome of 9 dogs treated with stereotactic radiation therapy for primary or metastatic vertebral osteosarcoma. Vet Comp Oncol 2018;16:E152-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heidner GL, Page RL, McEntee MC, et al. Treatment of canine appendicular osteosarcoma using cobalt 60 radiation and intraarterial cisplatin. J Vet Intern Med 1991;5:313-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Powers BE, Withrow SJ, Thrall DE, et al. Percent tumor necrosis as a predictor of treatment response in canine osteosarcoma. Cancer 1991;67:126-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Withrow SJ, Thrall DE, Straw RC, et al. Intra-arterial cisplatin with or without radiation in limb-sparing for canine osteosarcoma. Cancer 1993;71:2484-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

楼棪

上海长征医院骨科主治医师。研究方向为骨与软组织肿瘤的诊断与治疗,以第一作者身份发表SCI论文6篇,参编学术专著1部。2021年入选上海市青年科技英才扬帆计划。承担院级科研课题2项,医工交叉课题1项。授权发明专利1项,实用新型专利2项。(更新时间:2021/12/16)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Culp WTN, Rebhun RB, Alvarez EM, Malogolowkin MM, Randall RL, Thorpe SW. Canine osteosarcoma: where human and canine research intersect. Ann Joint 2020;5:30.