Evaluation and treatment of groin pain syndromes in athletes

Introduction

Groin pain syndromes, commonly referred to as sports hernias, are common in athletes, representing approximately 6% of all athletic injuries (1). They can be caused by a board range of pathologies including both visceral and orthopedic. However, many of causes are poorly defined and therefore are poorly understood. The term sports hernia is commonly used, which is non-descript and includes many pathologies that involve pain in the groin region of the athlete. However, groin pain has numerous causes, including injuries of the hip joint or abdominal wall. Likely, the difficulty of discerning different pathologies on both physical exam and imaging is partially to blame for the lack of concrete understanding. Further, varied nomenclature is used and the literature is comprised of mostly case series and opinions, many of which are in the general surgery and primary care literature.

Classification of these injury types have only recently been agreed upon. Nevertheless, the orthopedic surgeon should be well versed in the understanding and diagnosis of these issues as team physicians are responsible for proper treatment and if necessary, appropriate referral (2). Comprehensive understanding and consistent nomenclature are lacking but is essential for appropriate identification and treatment of this relatively common condition. The current manuscript attempts to define the different pathologies of groin pain syndromes, review the current literature, and provide recommendations regarding treatment and return to play.

Search strategy and criteria

Using medical subject headings and free-text words, a computerized database was conducted up to June 2019 and pertinent articles were cited. Subject-specific search was based on the terms sports hernia, athletic pubalgia, and groin pain. The quality and validity of the evidence was assessed based on journal prestige and impact factor as well as consistency with the other reviewed literature.

Main results

The reviewed literature was inconsistent in terms of terminology. Few comprehensive reviews exist combining intra- and extra-articular causes of groin pain syndromes in athletes. Further, little orthopedic literature exists regarding pathologic inguinal and abdominal wall conditions.

Results and discussion

Definitions

Typically, the term sports hernia refers to groin pain where the pathology is not caused by disturbances in the intra-articular hip joint, however, concomitant pathology in both locations are common. These pathologies commonly occur in physically active individuals and therefore have had numerous names which include sports hernia, groin pain syndromes, sportsman’s groin, athletic pubalgia, Gilmore’s groin, incipient hernia, core muscle injury, inguinal disruption, as well as several others (3-6). These non-descript terms, which include the word hernia, are misleading as no true hernia exists in these pathologies, although actual abdominal hernias can also occur. Some advocate for the term inguinal disruption or groin pain syndromes (5). Separating pathology based on anatomy is useful and suggested.

Due to the lack of literature and agreed upon definitions, the epidemiology of groin pain syndromes are difficult to ascertain. One study found that sports hernia was the primary diagnosis given in 95 of 189 patients (50%) with symptoms of chronic groin pain (7) while 40 of 50 patients (80%) with the diagnosis of groin pain of unknown etiology were found to have an actual hernia of the inguinal wall during surgical intervention (8). Patients should be thoroughly evaluated for an abdominal hernia as well, before using the term groin pain syndromes.

Anatomy

Knowledge of the complex anatomy of the groin is imperative for appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Understanding bony anatomy of the pelvis, hip joint, sacrum and coccyx as well as pubic symphysis with its fibrocartilaginous disc is essential. The locations of muscular, ligamentous, and tendinous attachments of the abdominal wall and thigh soft tissues are key and complex as they coalesce and attach in close proximity and require a cooperative balance. The location and direction of the forces of these attachments are critical to understand their equilibrium, pathology, and treatment.

Meyers’ group has categorized the evaluation of groin pain in three anatomic locations: anterior, posterior, and medial. The anterior compartment of the abdomen includes its musculature while the anterior compartment of the thigh includes the sartorius, iliacus, psoas, pectineus, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, and rectus femoris. The medial thigh is made up of the adductor muscles, gracilis, and obturator externus. The posterior compartment consists of the hamstrings and a portion of the adductor magnus (4,9).

Besides their role in movement, this musculature also plays an important role in force absorption during sport as significant torque is applied to both the pubic joint as well as the muscles and ligaments. The increased tension on these structures can lead to attenuation or tearing which can lead to pain. Range of motion can also be lost, which may further stress the pubic symphysis and hip joint possibly leading to injury (10,11). Meyers and colleagues argue that the disruption of the fine balance between these structures can consequently lead to symptoms. The rectus abdominis, adductor longus, and psoas are important structures in creating and dampining strain in this region. During fatigue or other causes of temporary loss of core control, imbalances can occur which may lead to injury.

Intra-articular hip structures also are affected by these forces and pathologies, most common being the anterior labrum of the hip. Therefore, both hip and non-hip joint pathologies can be present simultaneously and both should be evaluated. Nerve compression also can be symptomatic. One study of 36 patients who underwent radiofrequency denervation of the ilioinguinal nerve had significant pain relief (12). A detailed history and physical exam are essential to determine what the cause of the athlete’s deficiency or injury is, as a single pathology is not always the cause. The Layer Concept established by Dr. Bryan Kelly can simplify diagnosis of the complexity of multiple pathologies in a single anatomic region. Four layers are defined about the hip and include the (I) osseous layer, (II) inert tissue layer, (III) contractile layer, and (IV) neuromechanical layer (13). By discerning pathologies in each layer, one can better diagnose and treat one of multiple issues in the groin region.

Symptoms

The hallmark symptom of groin pain syndromes is a complaint of a deep groin or lower abdominal pain. The most common complaints include: (I) lower abdominal pain or groin pain, (II) pain worse with Valsalva or sport-specific activities including kicking, cutting, sit-ups and sprinting and that is relieved with rest, (III) tenderness to palpation over the pubic ramus, (IV) pain with resisted abdominal sit-ups, and (V) pain with resisted hip adduction (14). The pain is generally worse with exertion and is relieved with rest, but returns upon resumption of sports-related activities (15). Symptoms are typically insidious; however, if acute, athletes typically describe a pulling, popping, or tearing sensation at a specific time point.

The type and intensity of pain can vary significantly from aggravating to disabling. Some complaint of referred pain along the adductor longus tendon with forceful or resisted hip adduction and most report point tenderness over the superior-lateral pubis. Pain commonly also radiates into the inguinal ligament, testicular region, and perineum. Pain can be exacerbated by extended periods of sitting or when getting out of bed or into a car. Sudden acceleration, kicking, cutting, twisting, sprinting, and lateral movements typically reproduce symptoms most vividly with rest alleviating them (16). Valsalva movements such as sneezing or coughing also can worsen symptoms (16). If the adductor musculature is affected, active adduction or passive abduction of the hip exacerbates symptoms (17,18). Sharp, burning, stabbing, or electric like pain in the groin also can occur secondary to inguinal neuralgia (19).

Pathophysiology

Groin pain syndromes are characterized as pain located in the inguinal region of an athlete without an actual hernia and can be caused by a range of pathologies, many of which are poorly understood (6-8). It is associated with a number of pathologic findings, including attenuation or tearing of the transversalis fascia or conjoined tendon, abnormalities at the insertion of the rectus abdominis muscle, avulsion of part of the internal oblique muscle fibers at the pubic tubercle, tearing within the internal oblique musculature, or abnormality in the external oblique muscle and aponeurosis. These injuries alone or in combination may predispose an individual to a dilated and weakened internal inguinal ring, leading to development of athletic pubalgia (20).

The development of this condition is multifactorial and often is associated with overuse. One mechanism involves excessive stress in the pubic symphysial region. Instability of the symphysis itself can also be a cause. The pubic symphysis is the point on which a line connecting the femur and the lumbo-pelvo-sacral unit rotates (21). Imbalances in muscle group strength, endurance, coordination, or extensibility may exacerbate stresses in this region (20). Meyers et al. described an antagonistic relationship between the adductor muscles and rectus abdominis, which both insert onto the pubis, as being one cause for chronic groin pain (22). Anatomic studies have found these two structures are continuous when inserting onto the pubic symphysis (23). Restricted hip range of motion caused by impingement may also cause abnormal bending forces at the site of the pubic symphysis, further increasing stresses in this region. Increased stresses at the symphysis increases stress on inguinal tissue adjacent to the transversalis fascia, leading to pain and weakening of the inguinal ring (24). Additionally, the internal oblique and transversalis fascia attachments from the inguinal ligament may further be weakened by the repetitive action of the adductor musculature as it pulls against a fixed extremity (25).

Physical exam

A key physical examination finding of groin pain syndromes are pubic tubercle tenderness, while tenderness over the adductor longus tendon and/or the lower rectus abdominis is also common (19,26,27).

Patients may also have a palpable inguinal floor tear with pain inside the external inguinal ring. Pain may be reproduced during resisted sit-up with knees extended and feet flexed while the examiner palpates the insertion of the rectus abdominis.

A complete examination includes palpation of the pubic symphysis, the rectus abdominis muscle, the internal/external oblique muscles, the origin of the adductor muscles, the pectineus and gracilis muscle, and the inguinal ring for areas of tenderness. A regional exam also should be done to determine concomitant sources of pain including intra-articular and extra-articular hip pathology (14).

Assessment of the lumbar spine, sacroiliac joints, and hip joints for range of motion and tenderness should be performed. Examination while standing and supine is important to determine the presence of inguinal or femoral hernia. The testes and rectum should be examined for the presence of masses and the prostate for tenderness or bogginess. A gynecologic examination may be required in a female patient (14).

Imaging and diagnostic testing

Initial diagnostic imaging begins with AP pelvis and lateral hip radiographs. Although typically negative in isolated groin pain syndromes, they can rule out avulsion injuries about the pelvis, radiographic signs of bony impingement, stress fractures, osteitis pubis, sacralized lumbar vertebrae, neoplasms, and other potential sources of pain. Pelvic radiographs may show sclerosis and widening at the pubic symphysis caused by symmetric bone resorption (6).

Nuclear medicine studies such as Tc 99m bone scans, although not specific, may help diagnose concomitant pathology in the superior pubis, pubic symphysis, or adductor tendon origin in the setting of a conjoined tendon injury (28). As with plain radiographs, bone scans do not help establish the diagnosis but can be useful for ruling out other conditions, such as osteitis pubis, symphyseal instability, osteoarthritis, and tumor (19).

MRI is the current gold standard for evaluation of activity-related pelvic pain. It sensitive in diagnosing bone marrow edema about the pubic symphysis, indicating osteitis pubis. Bone marrow edema typically manifests in one of two patterns. The first, often seen in adolescents, involves both pubic bodies with fluid signal within the symphysis with edema extending symmetrically into the surrounding soft tissues. The second, observed in skeletally mature athletes, involves focal and asymmetric edema involving the anteromedial pubis, anterior capsule, capsular ligaments, and the aponeuroses of the adductor longus and rectus abdominis (5). MRI is also useful in diagnosing stress fractures, tumors, avascular necrosis, as well as ruling out intraarticular hip abnormalities such as labral tears and articular cartilage defects.

A dedicated athletic pubalgia MRI protocol, including large and small field of view images focusing on the pubic symphysis, is useful for accurate diagnosis. The most frequent finding on MRI is fluid signal extending from the anterior-inferior insertion of the rectus abdominis into the adductor origin. When comparing MRI findings to findings at the time of surgery, Zoga et al. showed that MRI had a sensitivity and specificity of 68% and 100% for rectus abdominis tendinopathy and 86% and 89% for adductor longus tendinopathy (29). Albers et al. demonstrated that subtle defects in the fascial layers of the abdominal wall may be detectable on MRI. These findings correlated to findings at the time of surgery (30).

Herniography, radiographs after injection of radiopaque dye into the abdomen, is another imaging modality gaining popularity in Europe. However, it is invasive with complication risks and has low specificity (31). The technique provides an anatomic outline of the pelvic floor and its peroneal reflections and can identify small inguinal canal tears (31,32).

Dynamic ultrasonography, although operator-dependent, has shown promise as it allows real-time visualization of the inguinal canal. A defect in the transversalis fascia may be detected with activities such as the Valsalva. Orchard et al. used dynamic ultrasound to image 35 Australian football players for posterior wall deficiency. The study found that individuals with prior history of significant groin pain had 8 times higher relative risk of having bilateral posterior wall deficiency (33).

Diagnostic injections can also help determine the etiology of pain when conflicting results appear on clinical examination. Persistent pain in the groin or lower abdominal regions after intra-articular injection can be consistent with concomitant or isolated athletic pubalgia. Anesthetic injection into the pubic symphysis, adductor cleft, or psoas bursa also can aid in identifying associated or concomitant pathology (34).

Differential diagnosis

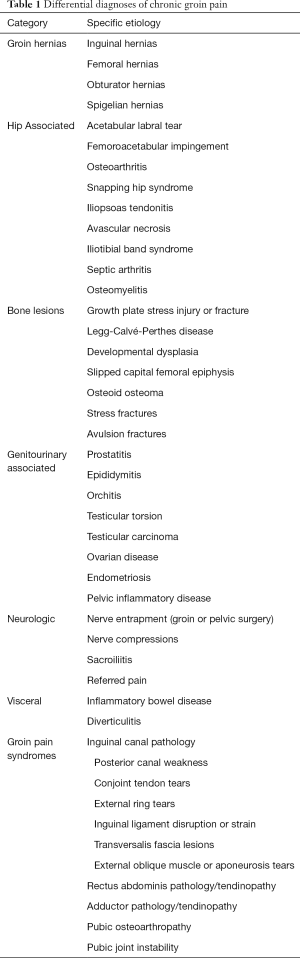

The differential diagnosis for groin pain is broad, therefore knowledge of anatomy combined with history and physical examination are key. These include intra-abdominal pathology such as inguinal hernias, urogenital pathology, spine pathology, sacroiliac pathology, hip joint pathology, bursitis, muscle or ligament strain, nerve entrapment, pelvis floor pain, and tumor (Table 1). Commonly, athletes have more than one diagnosis contributing to their symptoms, such as femoral acetabular impingement (FAI) with groin pain syndromes. This has been reported as high as 86%. These authors found patients treated with athletic pubalgia surgery alone but had underlying untreated FAI, had poor outcomes. This outlines the importance of proper treatment of all pathologies which can become complex as multiple diagnoses are possible (35).

Full table

Treatments

Non-operative

Initial treatment includes rest and avoidance of provoking activities. Physical therapy regimen involves stretching in the initial 2 weeks, followed by core strengthening and resolving imbalances between pelvic and hip stabilizers in the second 2 weeks. NSAIDs and ice can be used to minimize swelling and pain during the rehabilitation period. These treatments are generally done for at least 3 months. If substantial improvement is achieved, nonsurgical treatment is continued with functional rehabilitation followed by gradual sport-specific activity progression. Athletes typically return to sport at 10–12 weeks if pain-free. If no improvement is seen by 3 months, surgery may be considered (36).

Operative

Surgical treatment should be considered with persistent symptoms after a minimum of 6 weeks of non-operative treatment and in the absence of other identifiable causes of pain. Patients with suspected groin pain syndromes should be referred to an experienced general surgeon. Operative intervention includes open primary repair without mesh application, open repair with mesh application, and laparoscopic repair with mesh. Several techniques have been described for meshless open repair. Meyers et al. described open plication of the rectus abdominis fascia to the pubic bone and the inguinal ligament in order to provide stability to the pubis (37). Muschaweck reported division of the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, which is thought to be a major pain generator in athletic pubalgia, along with a tension-free repair of the transversalis fascia. A “collar” is also created using the internal oblique muscle around the neurovasculature of the internal ring to prevent nerve irritation and recurrent pain (38). Both procedures have yielded excellent clinical results.

Open and laparoscopic mesh repairs involve tensionless reinforcement of the deficient posterior inguinal wall and have yielded satisfactory outcomes with rates of symptomatic relief and return to sport varying between 63–97% (19). Open repairs may be performed under local anesthesia with or without resection of the ilioinguinal nerve while laparoscopic repair have the theoretical advantages of earlier return to sport (39-41). Most return to sport within 2–6 weeks after laparoscopic repair and within 1–6 months after open repair. In a randomized control trial by Ekstrand et al., 66 male soccer players with athletic pubalgia were divided into 4 intervention groups: (I) surgical repair, (II) physical therapy with lower abdominal strength training and anti-inflammatory medication, (III) physical therapy with daily strength training, and (IV) activity modification. Only the surgical repair group had a significant reduction in symptoms with jogging, kicking, and sprinting at 4 months (42). Paajanen et al. conducted a randomized control trial of 60 patients with chronic groin pain who were randomized to either endoscopic repair using mesh or physiotherapy. There was a 23% crossover rate from physiotherapy to surgery at 12 months, with return to sport being 90% in the surgery group compared to 27% with physiotherapy alone (43). Treatment of symphysis instability also may be warranted. In an athletic population, laparoscopic stabilization with a suture anchor configuration is a viable option (44).

Repair or lengthening of the adductors also can play a significant role in groin pain syndromes. Recent anatomic studies have found that the adductor longus is continuous with the rectus when inserting onto the pubic symphysis (23). For this reason, the adductors should also be carefully evaluated and treated. Historically, complete adductor tenotomy was performed which led to weakness and poor outcomes (45). Partial release does play a role in chronic cases which allows pain relief without loss of strength. However, recurrence is common and long-term pain relief is not well established (46). In acute cases, adductor longus repair with suture anchors is currently recommended as successful return to play with high patient reported outcomes have been reported in multiple studies (47-50).

The most common postoperative complication is edema in the abdomen, thighs, genitals and perineum. The incidence of wound infection and hematoma requiring reoperation are approximately 0.4% and 0.3%, respectively. Nerve dysesthesia has less than 1% occurrence rate and general affects the anterior and lateral femoral cutaneous, ilioinguinal, or genitofemoral nerve (4). The most common reason for re-operation for athletic pubalgia is the development of symptoms on the contralateral side, while the most common technical error leading to re-operation is inadequate adductor release or repair (4).

Patients also commonly have intra-articular hip pathology in which hip arthroscopy may be warranted. It is estimated that at least 50% of athletes with groin pain syndromes will have a labral tear and 86% will have radiographic evidence of FAI (35). Hammoud et al. found that over 30% of athletes requiring FAI surgery had previously undergone athletic pubalgia surgery. Almost 40% had symptoms suggestive of groin pain syndromes that resolved with FAI surgery alone (51). This creates a complex decision-making process in those without symptoms. Therefore, history and physical examination is key for treatment decisions with diagnostic injections in unclear cases with concerning imaging. If the hip is injected and pain subsides but persistent abdominal symptoms exist with a consistent history and physical examination, a patient may require both surgical interventions. Larson et al. reported on 37 professional and high-level college athletes with findings of both FAI and groin pain syndrome where 25% returned to sport if only groin/abdominal surgery was performed, 50% if FAI surgery alone was performed, and 89% if both occurred (52). Hammoud et al. reported similar results in 39 professional athletes with 0% returning after groin pain surgery alone, 39% with FAI surgery alone, and 100% after both surgeries (51). These two studies also found that if FAI surgery was done alone, 39–50% of athletes had resolution of their groin pain syndrome further complicating the situation (51,52). This leads to a complex decision between the patient and the physician which requires in depth patient education and discussion. The authors do not treat asymptomatic pathology seen on imaging but may consider adding hip arthroscopic treatment with large cam lesions in those at risk of large cartilage delamination if groin pain syndrome surgery is being performed.

Conclusions

The precise sequence of events that leads to development of groin pain syndromes is unclear. However, it is thought to be associated with a number of factors, including imbalances in abdominal and hip adductor strength, deficits in hip range of motion, poor tissue extensibility, and high intensity or high repetition hip adductor muscle shearing. History and physical remain central to the appropriate diagnosis combined with imaging modalities such as MRI, CT, and diagnostic ultrasound due to difficulty of diagnosis. The most common surgical finding is posterior inguinal wall insufficiency leading to occult hernia. If a trial of physical therapy and rest fails, current literature suggests referral to an experienced general surgery for surgical consideration which typically yields successful outcomes. The optimal technique is up for debate, with laparoscopic repair possibly allowing faster return to sport.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflict of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aoj.2020.01.03). CSM is a consultant for Arthres. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Suarez JC, Ely EE, Mutnal AB, et al. Comprehensive approach to the evaluation of groin pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2013;21:558-70. [PubMed]

- Zoland MP, Maeder ME, Iraci JC, et al. Referral patterns for chronic groin pain and athletic pubalgia/sports hernia: magnetic resonance imaging findings, treatment, and outcomes. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2017;46:E251-6. [PubMed]

- Kingston JA, Jegatheeswaran S, Macutkiewicz C, et al. A European survey on the aetiology, investigation and management of the "sportsman's groin". Hernia 2014;18:803-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyers WC, McKechnie A, Philippon MJ, et al. Experience with "sports hernia" spanning two decades. Ann Surg 2008;248:656-65. [PubMed]

- Sheen AJ, Stephenson BM, Lloyd DM, et al. 'Treatment of the sportsman's groin': British Hernia Society's 2014 position statement based on the Manchester Consensus Conference. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1079-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swan KG Jr, Wolcott M. The athletic hernia: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;78-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lovell G. The diagnosis of chronic groin pain in athletes: a review of 189 cases. Aust J Sci Med Sport 1995;27:76-9. [PubMed]

- Malycha P, Lovell G. Inguinal surgery in athletes with chronic groin pain: the 'sportsman's' hernia. Aust N Z J Surg 1992;62:123-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palisch A, Zoga AC, Meyers WC. Imaging of athletic pubalgia and core muscle injuries: clinical and therapeutic correlations. Clin Sports Med 2013;32:427-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rambani R, Hackney R. Loss of range of motion of the hip joint: a hypothesis for etiology of sports hernia. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2015;5:29-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strosberg DS, Ellis TJ, Renton DB. The role of femoroacetabular impingement in core muscle injury/athletic pubalgia: diagnosis and management. Front Surg 2016;3:6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Comin J, Obaid H, Lammers G, et al. Radiofrequency denervation of the inguinal ligament for the treatment of 'Sportsman's Hernia': a pilot study. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:380-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Draovitch P, Edelstein J, Kelly BT. The layer concept: utilization in determining the pain generators, pathology and how structure determines treatment. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2012;5:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Litwin DE, Sneider EB, McEnaney PM, et al. Athletic pubalgia (sports hernia). Clin Sports Med 2011;30:417-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kachingwe AF, Grech S. Proposed algorithm for the management of athletes with athletic pubalgia (sports hernia): a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008;38:768-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Larson CM. Sports hernia/athletic pubalgia: evaluation and management. Sports Health 2014;6:139-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harr JN, Brody F. Sports hernia repair with adductor tenotomy. Hernia 2017;21:139-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mei-Dan O, Lopez V, Carmont MR, et al. Adductor tenotomy as a treatment for groin pain in professional soccer players. Orthopedics 2013;36:e1189-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caudill P, Nyland J, Smith C, et al. Sports hernias: a systematic literature review. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:954-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farber AJ, Wilckens JH. Sports hernia: diagnosis and therapeutic approach. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2007;15:507-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verrall GM, Hamilton IA, Slavotinek JP, et al. Hip joint range of motion reduction in sports-related chronic groin injury diagnosed as pubic bone stress injury. J Sci Med Sport 2005;8:77-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyers WC, Yoo E, Devon O, et al. Understanding “sports hernia” (athletic pubalgia): the anatomic and pathophysiologic basis for abdominal and groin pain in athletes. Oper Tech Sports Med 2007;15:165-77. [Crossref]

- Davis JA, Stringer MD, Woodley SJ. New insights into the proximal tendons of adductor longus, adductor brevis and gracilis. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:871-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fricker PA. Management of groin pain in athletes. Br J Sports Med 1997;31:97-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cowan SM, Schache AG, Brukner P, et al. Delayed onset of transversus abdominus in long-standing groin pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004;36:2040-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Diesen DL, Pappas TN. Sports hernias. Adv Surg 2007;41:177-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Falvey ÉC, King E, Kinsella S, et al. Athletic groin pain (part 1): a prospective anatomical diagnosis of 382 patients--clinical findings, MRI findings and patient-reported outcome measures at baseline. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:423-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Le Jeune JJ, Rochcongar P, Vazelle F, et al. Pubic pain syndrome in sportsmen: comparison of radiographic and scintigraphic findings. Eur J Nucl Med 1984;9:250-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zoga AC, Kavanagh EC, Omar IM, et al. Athletic pubalgia and the "sports hernia": MR imaging findings. Radiology 2008;247:797-807. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Albers SL, Spritzer CE, Garrett WE Jr, et al. MR findings in athletes with pubalgia. Skeletal Radiol 2001;30:270-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sutcliffe JR, Taylor OM, Ambrose NS, et al. The use, value and safety of herniography. Clin Radiol 1999;54:468-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brierly RD, Hale PC, Bishop NL. Is herniography an effective and safe investigation? J R Coll Surg Edinb 1999;44:374-7. [PubMed]

- Orchard JW, Read JW, Neophyton J, et al. Groin pain associated with ultrasound finding of inguinal canal posterior wall deficiency in Australian Rules footballers. Br J Sports Med 1998;32:134-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elattar O, Choi HR, Dills VD, et al. Groin Injuries (Athletic Pubalgia) and Return to Play. Sports Health 2016;8:313-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Economopoulos KJ, Milewski MD, Hanks JB, et al. Radiographic evidence of femoroacetabular impingement in athletes with athletic pubalgia. Sports Health 2014;6:171-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Larson CM, Lohnes JH. Surgical management of athleticpubalgia. Oper Tech Sports Med 2002;10:228-32. [Crossref]

- Meyers WC, Foley DP, Garrett WE, et al. Management of severe lower abdominal or inguinal pain in high-performance athletes. PAIN (Performing Athletes with Abdominal or Inguinal Neuromuscular Pain Study Group). Am J Sports Med 2000;28:2-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muschaweck U, Berger L. Minimal Repair technique of sportsmen's groin: an innovative open-suture repair to treat chronic inguinal pain. Hernia 2010;14:27-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rossidis G, Perry A, Abbas H, et al. Laparoscopic hernia repair with adductor tenotomy for athletic pubalgia: an established procedure for an obscure entity. Surg Endosc 2015;29:381-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Veen RN, de Baat P, Heijboer MP, et al. Successful endoscopic treatment of chronic groin pain in athletes. Surg Endosc 2007;21:189-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown RA, Mascia A, Kinnear DG, et al. An 18-year review of sports groin injuries in the elite hockey player: clinical presentation, new diagnostic imaging, treatment, and results. Clin J Sport Med 2008;18:221-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ekstrand J, Ringborg S. Surgery versus conservative treatment in soccer players with chronic groin pain: a prospective randomised study in soccer players. European Journal of Sports Traumatology and Related Research 2001;23:141-5. (Testo Stampato).

- Paajanen H, Brinck T, Hermunen H, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for chronic groin pain in athletes is more effective than nonoperative treatment: a randomized clinical trial with magnetic resonance imaging of 60 patients with sportsman's hernia (athletic pubalgia). Surgery 2011;150:99-107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arner JW, Albers M, Zuckerbraun BS, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of pubic symphysis instability with anchors and tape suture. Arthrosc Tech 2017;7:e23-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akermark C, Johansson C. Tenotomy of the adductor longus tendon in the treatment of chronic groin pain in athletes. Am J Sports Med 1992;20:640-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schilders E, Dimitrakopoulou A, Cooke M, et al. Effectiveness of a selective partial adductor release for chronic adductor-related groin pain in professional athletes. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:603-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vogt S, Ansah P, Imhoff AB. Complete osseous avulsion of the adductor longus muscle: acute repair with three fiberwire suture anchors. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2007;127:613-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dimitrakopoulou A, Schilders EM, Talbot JC, et al. Acute avulsion of the fibrocartilage origin of the adductor longus in professional soccer players: a report of two cases. Clin J Sport Med 2008;18:167-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bharam S, Feghhi DP, Porter DA, et al. Proximal adductor avulsion injuries: outcomes of surgical reattachment in athletes. Orthop J Sports Med 2018;6:2325967118784898 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tansey RJ, Benjamin-Laing H, Jassim S, et al. Successful return to high-level sports following early surgical repair of combined adductor complex and rectus abdominis avulsion. Bone Joint J 2015;97-B:1488-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hammoud S, Bedi A, Magennis E, et al. High incidence of athletic pubalgia symptoms in professional athletes with symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement. Arthroscopy 2012;28:1388-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Larson CM, Pierce BR, Giveans MR. Treatment of athletes with symptomatic intra-articular hip pathology and athletic pubalgia/sports hernia: a case series. Arthroscopy 2011;27:768-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Arner JW, Li R, Disantis A, Zuckerbraun BS, Mauro CS. Evaluation and treatment of groin pain syndromes in athletes. Ann Joint 2020;5:17.